Reproduced below is an article from the www.psywarrior.com website, reproduced by kind permission of Sergeant Major Herbert Friedman, a specialist in psychological warfare (http://www.psywarrior.com/HerbBio.html).

It contains a history of propaganda operations against the Ho Chi Minh Trail, as well as methods of interdiction, including sensors, surveillance, leaflet drops and the successes of the ‘Open Arms’ programme. It also reveals details of ‘Operation Camel Path’, a MACV operation which targeted Viet Cong and NVA troops in Cambodia.

Our thanks to Peter Alan Lloyd for obtaining consent to its reproduction here.

PSYOP IN LAOS

SGM Herbert A. Friedman (Ret.)

During the decade the United States fought in Vietnam, it fought a second and perhaps deadlier secret war in Laos. I write “deadlier” because at the end of the war, North Vietnam released 591 prisoners under “Operation Homecoming,” but none came back from Laos. Of the over 500 American Servicemen listed as missing or prisoner-of-war in Laos, the Pathet Lao never released a single American military POW they captured and held at war's end. Even though credible reports established that numerous American military prisoners-of-war were alive at the end of the war, none came home.

The only American prisoner in Laos released at war’s end was Continental Air Service civilian pilot Emmet Kay in 1974. The CIA-sponsored air charter company flew supplies to Royal Lao Army troops as well as flying special missions to insert indigenous reconnaissance teams. The Pathet Lao shot him down (or he ran out of gas depending upon which story you believe) on 7 May 1973 as he flew six Lao military personnel to a government outpost near the Communist headquarters in Sam Neua. Although Emmet Kay claimed to have been shot down, other pilots in the air that day including Captain Jack Knotts of BirdAir monitored his radio calls and heard him claim that he was lost and getting short on fuel. Kay apparently took off from Laos Site (LS-272) at Ban Sorn. They released him on 18 September 1974 after 16 1/2 months in captivity.

There is some evidence that President Eisenhower considered Laos the most important Southeast Asian country of his domino theory, believing it might be even more important that Vietnam. In December 1960, Eisenhower concluded a high level meeting on Laos by stating that: We must not allow Laos to fall to the Communists, even if it involves war in which the U.S. acts with allies or unilaterally.

It was one of those wars that was fought for the right reasons but became a quagmire due to the political restraints placed on the combatants. The U.S. involved itself in Laos to help protect the Lao government against a Communist North Vietnamese invasion and occupation and to slow the movement of men and weapons from North Vietnam into South Vietnam. It was fought on the cheap by very limited armed forces, some civilians and a lot of mercenaries. It was almost successful. The problems arose when the government made a conscious decision to lie to the American public; to claim that the country was neutral, to claim that there were no U.S. troops in Laos and worse, to claim that no U.S. servicemen had been killed there. That was a lie that grew and grew and came back to turn the American public against its leaders and the war. Like the little boy that cried wolf, after American leaders were caught telling lie after lie, nothing they said was believed.

Map of Laos

This war seldom made the headlines and was mostly fought by Special Forces on the ground and the Air Force in the sky as the United States attempted to stem the flow of goods by interdicting travel down the “Truong Son Strategic Supply Route,” known to the Americans as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, while fighting a holding action against the Communist Pathet Lao. The US military assistance program provided Laos with equipment and advisors. Between 1962 and 1973, a total of $1.4 billion dollars of aid was provided.

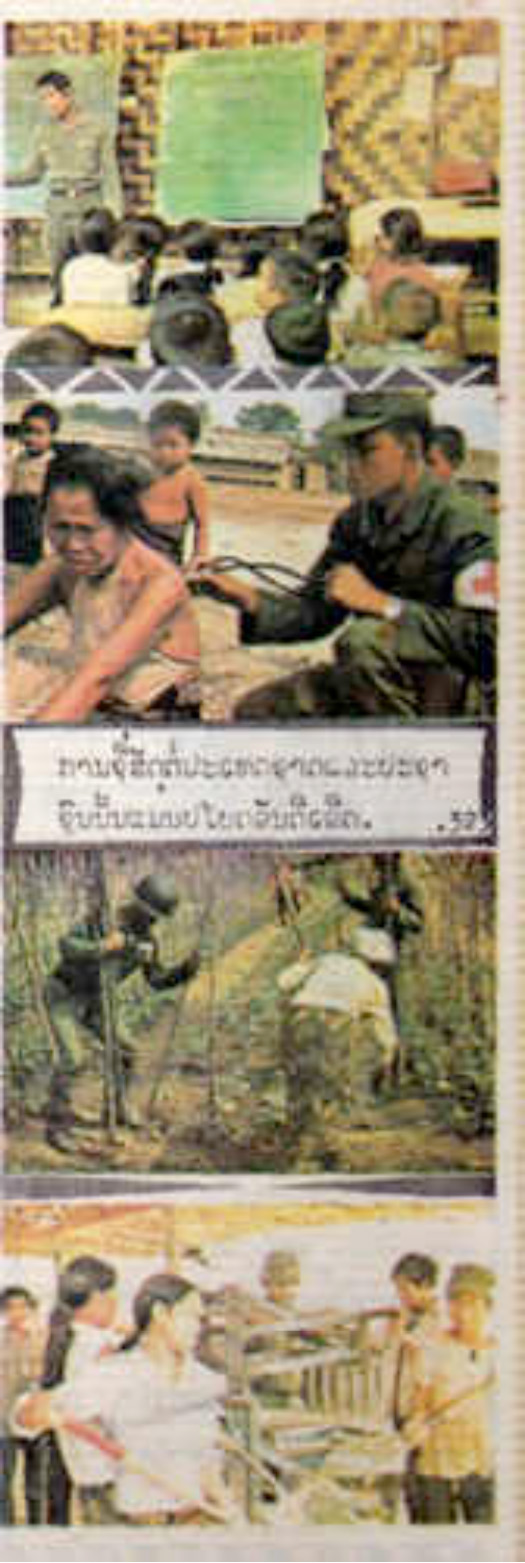

Some of the methods used by the Special Forces to win over the Lao people and soldiers were listed in a letter entitled “Civil Assistance” by Lieutenant Colonel John T. Little in September 1961. LTC Little mentions twelve rules that were to be followed to win the hearts and minds of the Lao people. One such rule is: An imaginative program of village assistance properly backed by the military and civil authorities is one form of psychological operation which will contribute significantly toward…achievement of U.S. goals in Laos.

The letter also went into some detail of other factors that could be used to win the loyalty of the Lao. Among them were; aid to education, sanitation, aid to agriculture, transportation improvement, children’s playgrounds, the distribution of special tools, improving the markets, American movies and electric lights. Little thought that in addition to training the Lao to protect themselves, his policies would bring rich psychological returns to the United States.

In regards to Air Force operations, they were severely handicapped according to U.S. Ambassador Godley: Never in the history of warfare has a military element been more shackled in its operation than was the USAF in Laos. The rules of engagement were voluminous, complex and precise. It could not engage any ground forces unless requested by the Lao government and approved by the Embassy. It could not bomb within one hundred yards of an inhabited dwelling, nor could it endanger inhabited villages. The types of ordnance it could use had to be improved…We were repeatedly charged with the indiscriminate bombing of civilians. Nothing could have been further from the truth…

A brief history of the early American action in Laos reveals that Operation White Star was a clandestine operation, under the auspices of the CIA, but thru the Ambassador to Laos to “assist” Laos in fighting the communists. The teams worked with the Laotian people, mainly the Hmongs and other ethnic groups. It was all designed to support Vang Pao’s clandestine army which was supported by the CIA (with Air America) under Project 404 and 603. It is alleged that the Hmong infantry grew to about 40,000 troops.

LTC Arthur D. "Bull" Simons

Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) “Bull” Simons was the Commander of the first team inserted in July 1959, code-named Hotfoot. He had selected, organized and trained Special Forces “A” teams from the 77th Special Forces Group (Airborne) based at Fort Bragg, NC. The mission was initially code-named Ambidextrous. All personnel were given intensive training and cross training. All personnel took daily language lessons in both French and Laotian. Once inside Laos, the teams were regularly replaced about every six months. Team II arrived in June 1960 commanded by LTC Magnus L. Smith. In November 1960, Team IV took over, commanded by LTC John Little, and on 28 January 61 it was augmented with a 12-man Psywar team under LTC Chuck Murray. In April of 1961, Team V replaced Team IV and was renamed White Star. In October 1961 LTC Bull Simons took command again. At its peak on 23 July 1962 when a Declaration of Neutrality was signed, the White Star strength was 433.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Turkoly-Joczik, Ph.D. says in an article entitled “Secrecy and Stealth: Cross-Border Reconnaissance in Indochina, Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin: The first series of U.S.-sponsored [Vietnamese troops] cross-border operations took place in 1964 under the code name “Leaping Lena.” The South Vietnamese Government under the supervision of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) conducted these activities. Unfortunately, Leaping Lena was a failure and was terminated.

The Special Forces losses in Laos between 1959 and 1962 from the 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) were SGT Gerald M. Biber, SGT John M. Bischoff, CPT Walter Moon, SGT Theodore Berlett, and SSG Raymond Parkes.

Readers who want to study this action in more depth are encouraged to read Land of a Million Elephants, by Asa Baber, Morrow books, 1970; The War in Laos, Kenneth Conboy, Osprey books, 1989; Code-name: Copperhead, Joe Garner, Simon & Shuster, 1994; and Operation White Star, Richard Sutton, Daring Books, 1990.

In 1962 a Geneva accord was signed that guaranteed the neutrality of Laos and called for all foreign soldiers to leave. The United States removed its 666 Special Forces advisors. The North Vietnamese considered it a great political victory and sent in more troops. Averell Harriman, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs said: North Vietnam broke the 1962 agreements before the ink was dry.

For some reason the United States decided to go on with the pretense there was no war in Laos. As a result, as it attacked the enemy troops with mercenaries and bombs, and even B-52 raids, but it could not make a good defense of its actions. It should have simply said “we are facing a determined enemy” and let the world know what was happening. For example, when President Nixon tried late in the war to explain, mistakes were made. Nixon said that there were 50,000 North Vietnamese soldiers in Laos and they had recently been joined by 13,000 more. The press reported 70,000 enemy troops. A United States Information Agency official said at a press briefing there were just 40,000 North Vietnamese in Laos. The American public said “huh?” This confusion made their leaders appear to be liars and further hurt the American cause.

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger went before the public and stated: No American stationed in Laos has ever been killed in ground combat operations.

Notice the disclaimers. “Stationed in Laos” meant that all the troops that crossed over from South Vietnam did not count. “Ground Operations” meant that he could ignore all the deaths from aircraft downed by the enemy. CIA people did not count because they were “invisible” anyway. The Thai mercenaries did not count because they were not American. We are not going to mention Thailand in this article, but keep in mind that at the height of their deployment there were about 17,000 Thais helping the U.S. in Laos.

Eventually the U.S. Government was forced to admit that about 200 Americans had been killed in Laos and another 200 were missing or taken prisoner. The tremendous number of lies told for so long convinced the American people their government could not be trusted and everything they said in regard to this war was a lie. It was all a terrible miscalculation by Washington.

Thomas A. Bruscino, Jr. discusses U.S. actions in Laos in the Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, paper Out of Bounds - Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare. The early efforts of the CIA and Special Forces included limited attempts to interdict the supply lines within Laos. Starting in 1961, a few specially trained South Vietnamese teams launched infiltrations across the border to gather intelligence. The next year, CIA officers began training Lao natives in basic reconnaissance of the communist road system. Both programs gathered general information, but neither provided specifics on the communist operation. A more direct approach came in 1964 when American advisers worked with South Vietnamese Special Forces on Operation Leaping Lena. Small teams of Montagnard tribesman led by South Vietnamese Special Forces were to cross into Laos to perform reconnaissance missions.

In January 1964, the Americans set up the Studies and Observations Group (SOG) within MACV, a special operations group that answered directly to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. SOG included men from all of America’s armed services, including Army Special Forces, Navy SEALs, and Air Force Air Commandos. SOG’s mandate included operations into Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam.

Infiltrations into Laos began in 1965, initially under the codename Shining Brass (in 1967 the name was changed to Prairie Fire). The teams included South Vietnamese troops led by American Special Forces personnel. Still concerned with violations of neutral territory, the men who went on these missions wore nondescript uniforms and carried untraceable weapons. They either crossed the border on foot or in unmarked Air Force helicopters, and similar helicopters would extract them at the end of missions. In 1966 they sent more than 100 teams into Laos; two years later, some 800 teams went into Laos and Cambodia combined.

The Air Force operations started with Barrel Roll in December 1964. The US Air Force and US Navy launched a series of escalating bombing missions against the communist infrastructure north of the DMZ in Laos. Barrel Roll was supplemented by Operation Steel Tiger in April 1965, but the latter began to spread the attacks to the eastern portion of the Laotian panhandle. Flying from bases in South Vietnam and Thailand, and off of carriers in the surrounding waters, American pilots flew nearly 800 missions against Laos in less than a month. The airpower interdiction program accelerated in the summer and fall of 1965, as the Air Force started working with the SOG incursions and the targeting area extended south to the Cambodian border. In December, the Air Force used B-52 bombers to hit targets in Laos, most notably the Mu Gia pass just north of the DMZ. Even the aerial defoliant program, Operation Ranch Hand, spread into the eastern portion of the Laotian panhandle.

USAF First Lieutenant Zot Barazzotto was one of the pilots that regularly flew over Laos using the call sign Covey 250 from March 1970 to March 1971. He told me: One morning I was coming in on the second flight and the guy before had found a trellised road that led to a little truck park. He could see the dent in the trees where they had been pulled down to cover the road that was cut below. We were beating up the area with what ordnance we could get but there wasn't much available because of Lam Son 719. The Covey OV-10 was usually armed with 4 pods of 2.75" rockets - 2 pods of 7 each white phosphorous (or “Willy Peter”) for marking targets and 2 pods of 7 each high explosive (HE) warheads. I turned west, armed the HEs and pulled the nose up so as to lob the rockets at the little supply dump. In rapid succession I shot all 14 HE rockets, 12 of which hit the supply dump with no apparent ill effects. Two rockets overshot the target and hit near the road, which was on a little ridge. I actually hit two trucks that were part of a convoy that had been stopped when they started beating up the bushes.

A 1966 Stars and Stripes article entitled “U.S. Psywar Unit Hitting Morale of VC in Vietnam” mentions the 6th PSYOP Battalion mission over the Mu Gia Pass: The Battalion has designed, printed, processed, loaded and delivered more than a half billion leaflets…We can print one million leaflets in support of any given mission within a 24-hour period. We printed three million leaflets on three different occasions in support of the Mu Gia Pass bombing in North Vietnam.

Colonel Perry L. Lamy, USAF, discusses the air campaign over Laos in Barrel Roll 1968-1973, An Air Campaign in Support of National Policy.

The nature of the conflict in Laos created a theater of operations separate from the rest of Southeast Asia (SEA). "Out-of-country" "up-country", "extreme western DMZ", "over-the-fence", and the "secret war" were terms used to characterize US military involvement in Laos.

In the southern panhandle, STEEL TIGER, involved the interdiction of the Ho Chi Minh Trail used by North Vietnam to prosecute their war in South Vietnam. In northern Laos a very different war was fought. BARREL ROLL provided air support for the ground forces of the Royal Lao Government (RLG) fighting Communist insurgents. The survival of the RLG and ultimately Laos as a neutral country was the object of this war.

Tactical aircraft used in BARREL ROLL for strike operations included USAF A-1, B-57, F-105, F-4, F-100, and F-111. Gun ships such as the AC-47, AC-119, and AC-130 were employed for truck interdiction and night air support to defend Lima Sites. The O-1, O-2, U-17, T-28, and OV-10 were used to provide visual reconnaissance and strike control. B-52 ARCLIGHT sorties were occasionally employed beginning in February 1970 against tactical targets with operational level results.

A system of almost 200 airfields called Lima Sites was developed during the early 1960s. Throughout the war, these Lima Sites proved vital to the ground operations of the Hmong irregulars.

A Highly Modified Navy NP-2H Neptune Aircraft

It was not just the Army and the Air Force that flew over Laos. The Navy was there too. Robert Zafran was a young Navy Lieutenant Junior Grade who flew the Ho Chi Minh Trail from August to December 1967. He was part of a joint Navy/CIA operation called “Muddy Hill” (Task Group 50.8) that flew highly modified Navy Neptune aircraft equipped with state of the art electronics that included infrared detection, low illumination television, starlight scope, terrain following radar, a 70mm reconnaissance camera, electronic countermeasures, and active magnetic anomaly detection systems from Udorn Thani Royal Thai Air Force Base on low level, night reconnaissance combat missions over Laos and the Ho Chi Minh Trail.The aircraft were painted with a high-gloss "black widow black" paint (first used by WWII U.S. night-fighters). Some of these aircraft later were assigned to VO-67, which is mentioned in the next paragraph.

Another of the secret units designated to drop the sensors was U.S. Navy Observation Squadron 67. The members called themselves “the Ghost Squadron.” They flew from Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base, just across the Mekong River from Laos. Their primary mission was over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, but they also performed missions in South Vietnam. They also flew the Lockheed P-2 Neptune, a 1950s-era anti-submarine patrol airplane from Thailand into Laos and dropped camouflaged sensors along the trail. The squadron's planes were heavily modified for the mission, including the addition of M-60 machine guns, an armored belly and a jungle-green paint scheme.

We should note here that the 1971-1972 MACVSOG Command History – Index B says that Prairie Fire was later known as Phu Dung. It explains that: This was the SOG operation of reconnaissance and interdiction to counter infiltration of enemy forces through Laos. U.S. and Vietnam Air Force aircraft were authorized to infiltrate, exfiltrate and resupply Phu Dung forces. U.S. tactical air, fixed wing and rotary wing gun-ships were authorized to employ within the full depth of the Phu Dung Area of Operations to exploit targets of opportunity…Phu Dung is the name of the illusion appearing to opium smokers, a widely produced commodity in Laos.

The Department of State U.S. Foreign Relations Series Laos Volume (1954-1968) adds: The United States increasingly became involved in fighting a war against Pathet Lao/North Vietnamese forces in Laos during the Johnson administration. Laos, a small, poor, sparsely-populated kingdom, became entangled in the Vietnam war because of its geographic position. The Kennedy administration had hoped to neutralize Laos and insulate it from the conflict, but failed because of North Vietnam's insistence on controlling the infiltration routes into South Vietnam. During 1964-1968, During the first few months of 1964, the Pathet Lao/North Vietnamese forces again threatened the Plain of Jars, the strategic gateway to the Mekong valley, where most of the Lao population lived. Johnson and his advisers considered sending U.S. troops to Thailand as had been done in 1962, but settled instead on a series of incremental steps that included sending Air America pilots and propeller driven T-28 planes to reinforce the fledgling Lao Air Force and upgrading the Lao Air Force's bombing capabilities.

Differences of opinion in the administration arose over Laos policy. The Department of Defense and General Westmoreland wanted to carry the secret war across the border against the Ho Chi Minh trail. The Department of State and Ambassador Leonard Unger feared such a plan would shred what remained of the 1962 Geneva Accords and topple neutralist Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma. The Central Intelligence Agency concentrated on its "quiet war," supporting, supplying, and directing Hmong guerrillas to harass the North Vietnamese in Laos.

Despite continued differences of opinion among U.S. policy makers, after 1965 the trend was one of steady escalation of the war in Laos…Vietnam Commander William Westmoreland expanded covert cross border operations into Laos by South Vietnamese troops led by U.S. Green Berets. The secret air war against the Ho Chi Minh trail and in the north of Laos expanded exponentially.

Colonel Lamy adds: There were a variety of reasons for covertness. The ruse of neutrality was primary, along with the desire of the US to avoid embarrassing the Soviets. Since Khrushchev and Kennedy had jointly agreed on Laotian neutrality in 1961, overt involvement by the US in Laos would have forced the Soviets to respond directly. Overt action or public disclosure of US involvement would then force the Soviets to “close ranks†with their communist brothers. The Soviets were satisfied to "look the other way" in order to limit Chinese hegemony in Southeast Asia.

Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Marshall Green said in his 7 November 1964 paper “Immediate Actions in the Period Prior to Decision.”

There are now 27 T-28 aircraft in Laos, of which 22 are in operation. CINCPAC has taken action…to build this inventory back up to 40 aircraft…

In recent weeks, the T-28’s have been dropping a large number of surrender leaflets on many of their missions. These have already led, in some cases, to Pathet Lao defections.

We should also mention a very strange and prophetic war game that was played by United States Joint Chiefs of Staff in the National Military Command Center in 1963. The results of the game were absolutely correct, but as so often happens, contested by some military officers and ignored by the politicians. The play was to cover 10 years, and determine what would happen if the United States became involved in Vietnam. At the end of the decade, 1972 in game time, the North Vietnamese controlled all the countryside in South Vietnam, had taken over Laos, and had complete freedom of movement in Cambodia. During the game the USAF had heavily bombed the enemy and 500,000 American troops were deployed. As might be expected, Air Force General Curtis LeMay contested the results stating that his aircraft could bomb the Vietnamese back to the Stone Age. He also believed that American camps and installations could be protected from guerrilla attacks. In fact, the results of the game were exactly correct and over 50,000 U.S. lives might have been spared if someone had paid attention.

One sometimes wonders why they bother to play these games. I like to use personal anecdotes when I can and recall that at one time I took part in a war game that was played on an annual basis. I recall one unit being destroyed and a full bird colonel being told his unit was gone. He got very upset and told everyone in a loud voice, “I didn’t bring my staff all the way here to be knocked off the board on the first day.” Apparently he made enough noise; the monitors placed his unit back into the game.

This is just a brief review of what was going on in Laos. We will not attempt to tell the story of that war. That is a job for a military tactician. We will describe and depict some of the psychological warfare leaflets used in Laos to demoralize the communists and to motivate the Royal Lao Armed Forces and the Lao people.

Long Tieng

An Air Commando who was stationed at LS-20A (Long Tieng) and LS-153 (Mouang Kassy) told me:

Those of us who fought the war from Laos have always considered it to have been more important than the coverage indicated. But since the whole mess was classified as “never happening” and those who fought there “didn't exist” it is no wonder that most people who are knowledgeable about the war in Viet Nam will dismiss Laos as a sideshow.

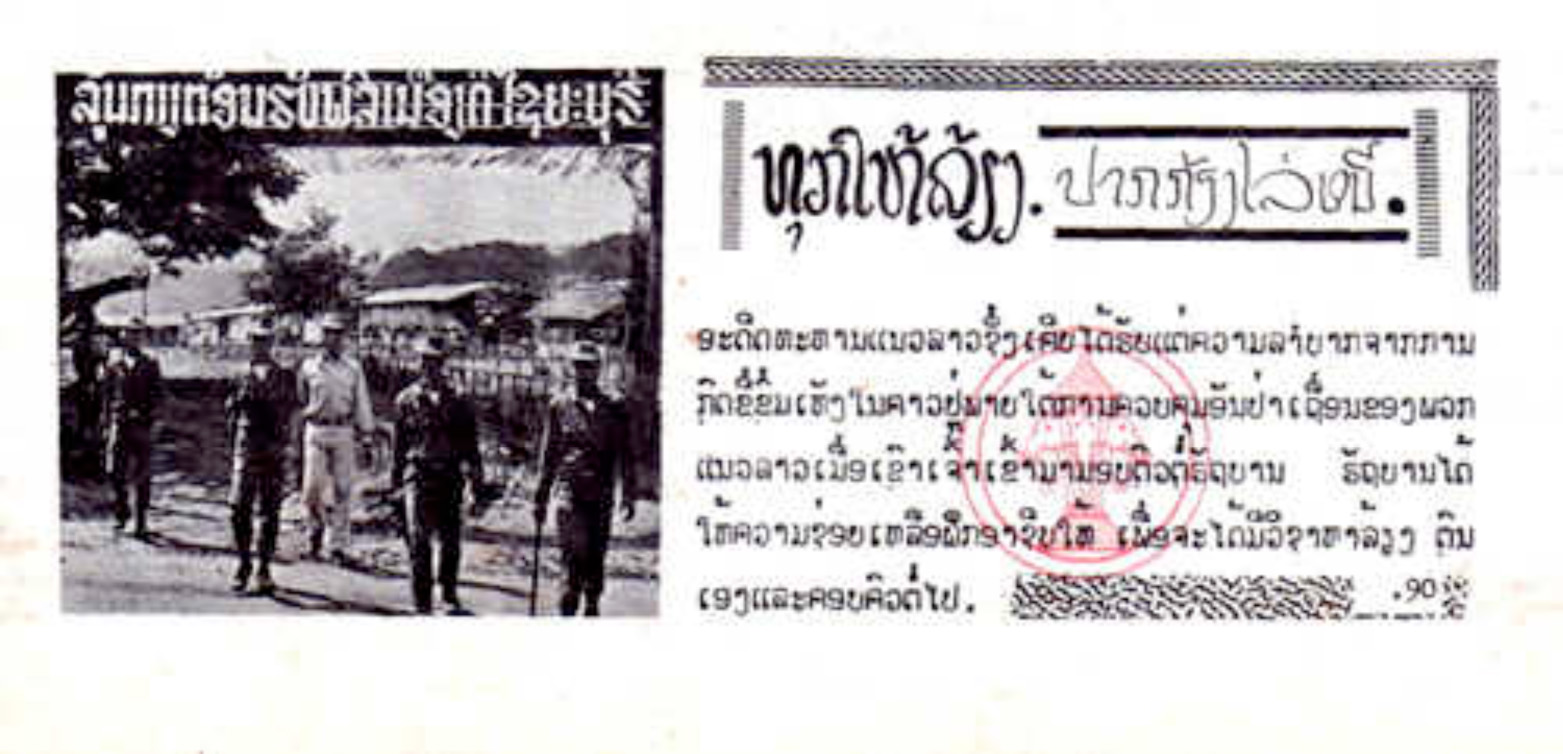

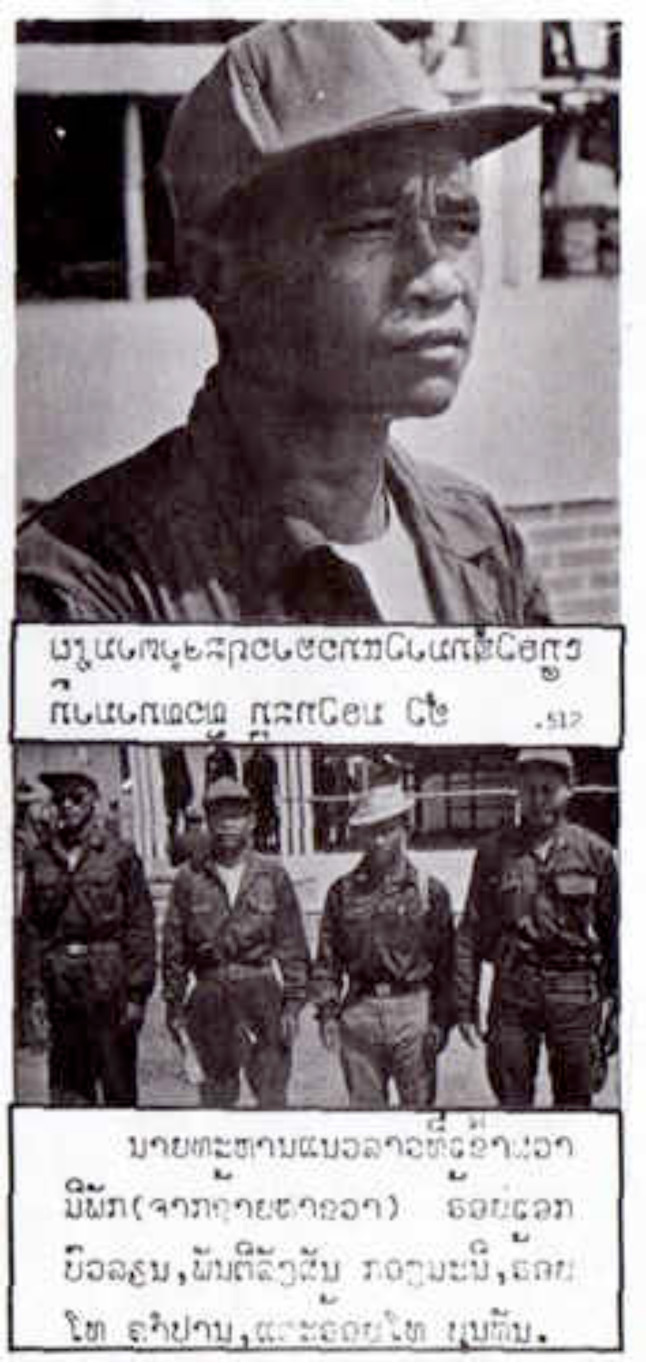

Hmong General Vang Pao, some of his Staff, Thai and CIA Officials

Hmong General Vang Pao, holding hands with Thai Army Chief Of Staff, Surakij Mayalab, overlooking Hmong-CIA headquarters, Long Tieng, Laos. To the left of Surakij Mayalab with shaved head is CIA case officer, Burr Smith. The rest of the men in the photo are Thai, from the elite CIA trained unit call PARU, or Police Aerial Reinforcement Unit, and Royal Thai Army, both of which served in Laos with Lao-Hmong forces.

Laos regained limited independence from France on 19 July 1949 as a constitutional monarchy and full independence at the end of 1954. The nation consisted of political ideologies from communist to conservative to neutralist. The Communist forces were made up of Prince Chao Souphanouvong (The Red Prince), Kaysone Phomvihane, the Pathet Lao and their North Vietnamese allies (supported by Red China and the USSR). The pro-Western forces included King Savang Vatthana, Prince Boun Oum, General Phoumi Nosavan and the Hmong guerrillas and militia led by General Vang Pao (backed secretly by the U.S. Government and its Central Intelligence Agency). The neutralists consisted of Prince Souvanna Phouma, General Kong Le, and the Royal Lao Government.

Prince Souvanna Phouma

Conflicts among neutralist, communist, and conservative factions led to increasingly chaotic and violent conflicts, particularly after 1960. The formal Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos, signed on 23 July 1962, provided for a coalition government and the withdrawal of all foreign troops from the country by 7 October, and the three factions formed a coalition government with Prince Souvanna Phouma as premier.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail

Out of Bounds: Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare

Thomas A. Bruscino, Jr.

By 1964, the communist Pathet Lao had withdrawn from the coalition and renewed guerilla actions with support from North Vietnam. With the war heating up in Vietnam, the United States got more deeply involved in Laos by interdicting traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and trying to force North Vietnam to pull some front-line units out of Vietnam and into Laos. In addition, the United States had aircraft and communication bases in Laos, including the 4500-foot elevation Lima Site 85 (Pha Thi), loaded with modern electronic equipment to aid the USAF in its missions over North Vietnam.

Laos was divided into five Military Regions (MR). MR I was in the northwest, including Luang Prabang and the borders with Burma and China; MR II was in the northeast, including Long Tieng, Sam Neua and Sam Thong; MR III consisted of the central panhandle region, including Savannakhet and much of the Ho Chi Minh trail. MR IV was in the south, including Pakse and the Bolovens Plateau; finally MR V consisted of the neutral zone around Vientiane.

Early in the war, there were plans to use local Lao tribes as part of an American-led resistance movement. This plan was forwarded to American Ambassador Sullivan who was concerned that it might be impossible to limit and control such an operation. Furthermore, if the resistance got into trouble, there would be no way to militarily support them, which might result in their very embarrassing slaughter.

Turkoly-Joczik mentions Sullivan in his paper:

The name of the first series of SOG patrols into Laos was “Shining Brass” (later renamed “Prairie Fire”) conducted between 1965 and 1969. These patrols began when intelligence reports indicated that the Ho Chi Minh Trail was expanding to meet the increasing demand for men and material in the South. To determine the nature and location of these activities in Laos, the OPS-35 forces conducted reconnaissance missions with units known as “Spike Teams” comprising six to twelve men (two to four U.S. personnel and four to eight indigenous personnel).

The U.S. Congressional Record of September 1973 revealed the increasing frequency of Prairie Fire missions when it disclosed that between September 1965 and April 1972, SOG conducted 1,579 reconnaissance patrols, 216 platoon-sized patrols, and three multi-platoon-sized operations in Laos.

The Prairie Fire operations were always subject to the approval or disapproval of the U.S. Ambassador in Laos, William H. Sullivan. Sullivan’s behavior and actions earned him some enmity from the U.S. military and he was frequently referred to as “the field marshal.” General William Westmoreland noted an example of the difficulties experienced with the Ambassador when he said, “Bill Sullivan had a tendency to impose his own restrictions over and above those laid on by the Department of State. We sometimes referred to the Ho Chi Minh Trail as Sullivan’s Freeway.”

Sullivan’s concern about the SOG’s operations stemmed from his desire to ensure that civilians did not become casualties from any misdirected attacks. He was also concerned about how the Soviet Union might interpret America’s military actions. Sullivan enjoyed a close personal relationship with the Soviet Ambassador to Laos, Boris Kornissovsky.

Most people believed that the Lao guerillas were in charge of their anti-government war but if we are to believe authors Paul F. Langer and Joseph J. Zasloff in North Vietnam and the Pathet Lao – Partners in the Struggle for Laos, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1970, that is not exactly true. The authors point out that the Lao Communists were trained, led, paid, and armed by the Vietnamese. In fact, we find the same comments that we heard from American advisors training South Vietnamese soldiers. The Americans said that the South Vietnamese were not patriotic, not motivated and very likely to desert in a fire fight. The exact same language is used by North Vietnamese advisors to the Pathet Lao. One North Vietnamese officer said that if a Vietnamese soldier ever admitted that he wanted to desert he would be immediately brought before a tribunal, and if he did desert and return home, his family would be shamed and lose “face.” If a Lao soldier said the same thing, it would be ignored, and if he returned home his family would rejoice that he escaped from the war.

Amidst the Vietnam War in 1970, the U.S. increased its military activities, but after Pathet Lao military gains, in May 1975 the Royal Lao government forces ceased fighting and the Pathet Lao took control. A Lao People's Democratic Republic, strongly influenced by Vietnam, was proclaimed 3 December 1975. The Republic of Vietnam and the United States Government directed several PSYOP campaigns targeting enemy troops in both Laos and Cambodia

LEAFLETS

The Republic of Vietnam and the United States government directed several PSYOP campaigns targeting enemy troops in both Laos and Cambodia. Before we discuss the leaflets dropped on the Laotians, we should mention that many of the Allied PSYOP leaflets were also dropped on Vietnamese troops who were coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos. Some were all in Vietnamese text; others had Vietnamese on one side and Laotian on the other side. About a dozen of the trail leaflets coded with a “T” mentioned Laos. We depict three below.

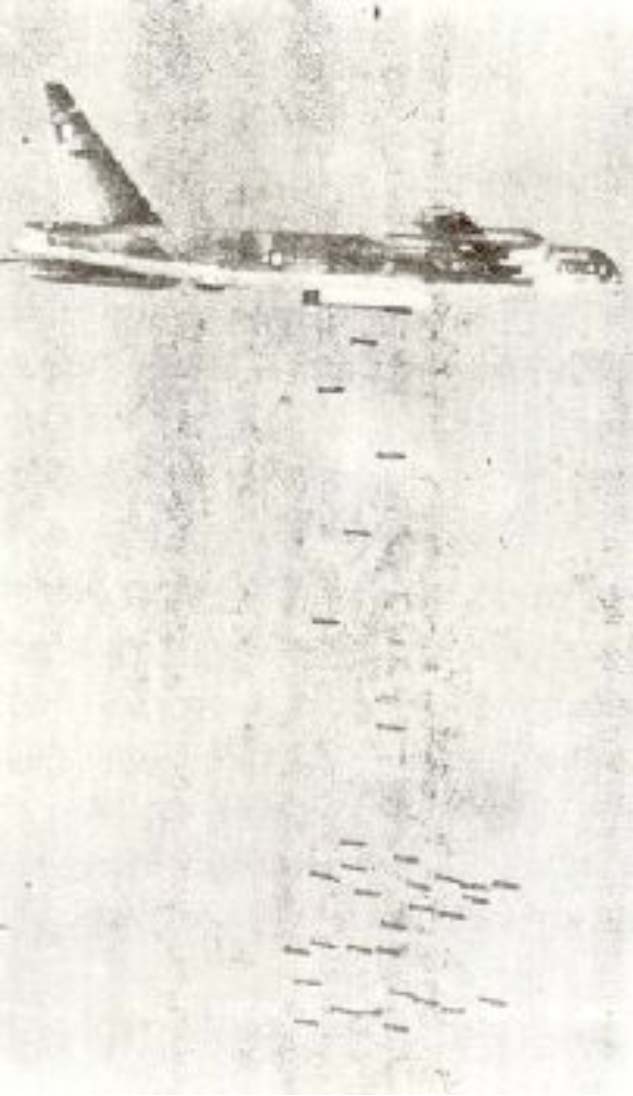

Leaflet T-07

Leaflet T-07 is a threat leaflet that warns the soldiers walking south of the terrible might of the American B-52 bomber. It was produced in two versions, one horizontal and one vertical. Fifteen million copies in all were printed and disseminated. The front of the leaflet depicts a B-52 dropping bombs. The back is all text:

YOU WILL NEVER SEE ONE OF THESE

You probably won't hear it. It flies too high. It is a B-52 bomber, used by the South Vietnamese people's powerful American allies to blast aggressors out of their hiding places. One B-52 carries 29,700 kilos of bombs and can drop them with pin-point accuracy, dealing certain death to everyone within the target area. The B-52 can strike you at any time during all seasons and weather conditions.

Your chance to avoid this fate will come. Look for your safe conduct pass.

This leaflet is specifically mentioned by Stanley Sandler in Cease resistance: It’s Good for You: A History of U.S. Army Combat Psychological Operations, 1999. Sandler adds:

A scrawled note on the translation sheet of this leaflet warns “Not to be used in Laos – per order of the Ambassador.” The bombing of Laos was a secret at the highest political levels.

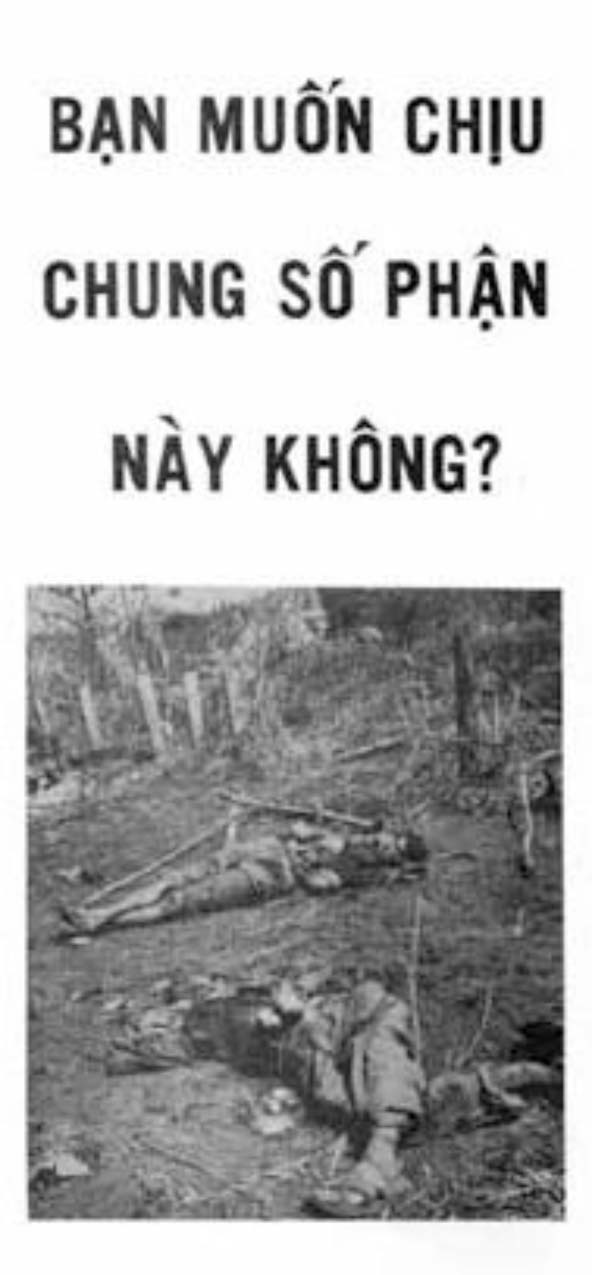

Leaflet T-62

The theme of death on a foreign battlefield, far away from your own home and ancestors was a very popular subject of many PSYOP leaflets. A number of the Trail leaflets pictured dead bodies that would never be properly buried and whose soul would walk the Earth forever as a result. I chose this one because it seemed especially poignant. It depicts two dead enemy soldiers and the text:

WILL YOU MEET THIS FATE?

The back is all text:

WILL YOU DIE IN LAOS FAR FROM YOUR ANCESTRAL HOME?

Why die needlessly in a foreign country? The people of Laos urge you to stop fighting and temporarily join the Royal Lao Government. You will be warmly welcomed and you will be returned home when the war is over.

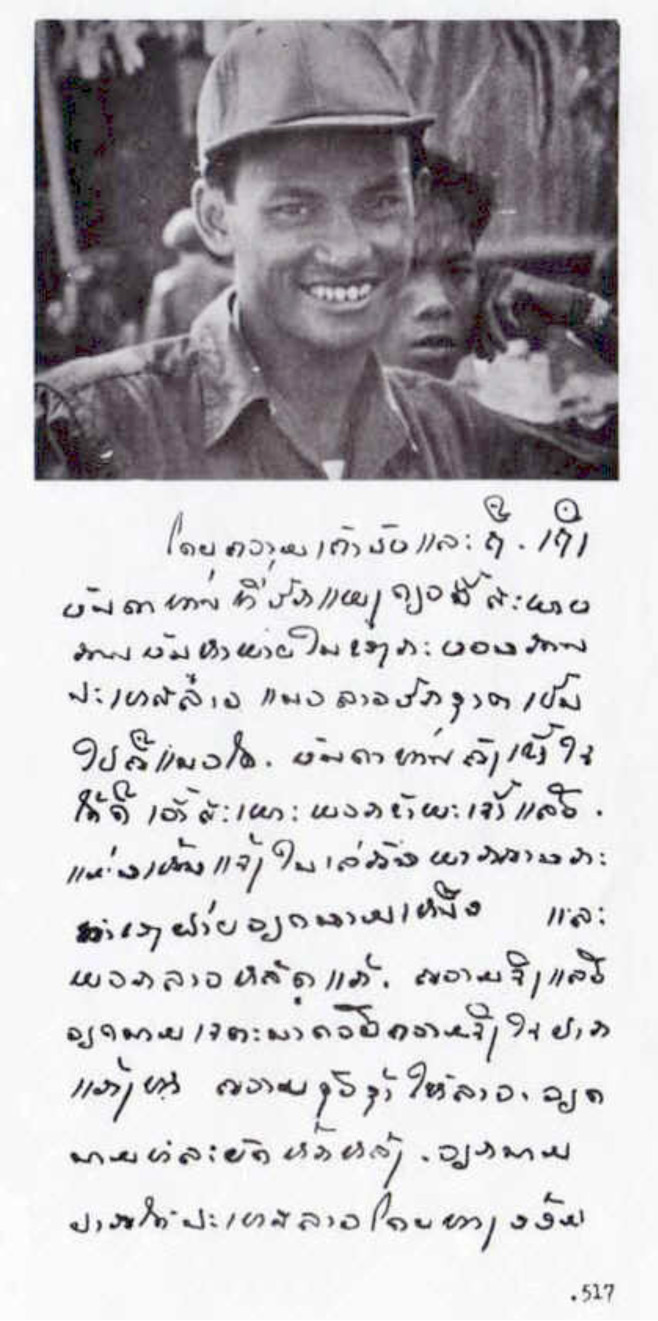

The threat of not being buried near your ancestral home and having your spirit wander forever is found in dozens of propaganda leaflets. The allies used just such a campaign after the mysterious death of Pathet Lao general Phomma Douangmala in 1970. The C.I.A. claimed that the North Vietnamese had murdered the general and then left his body unburied. In addition, loudspeaker aircraft flew over Pathet Lao sites playing ghost music and a message allegedly in the voice of the dead general. We mention this kind of operation in more depth in The Wandering Soul PSYOP Tape of Vietnam. This campaign was very successful. A number of the general’s loyal troops defected to the National Government. One was Captain Thao Boualiene, Commander of the 25th Battalion, who went over to the Government with a platoon of soldiers. You will see a photograph of the captain on leaflets .511 and .520 near the end of this article. Bouanien gave information that allowed the USAF to bomb a North Vietnamese base camp. Later, his entire battalion defected.

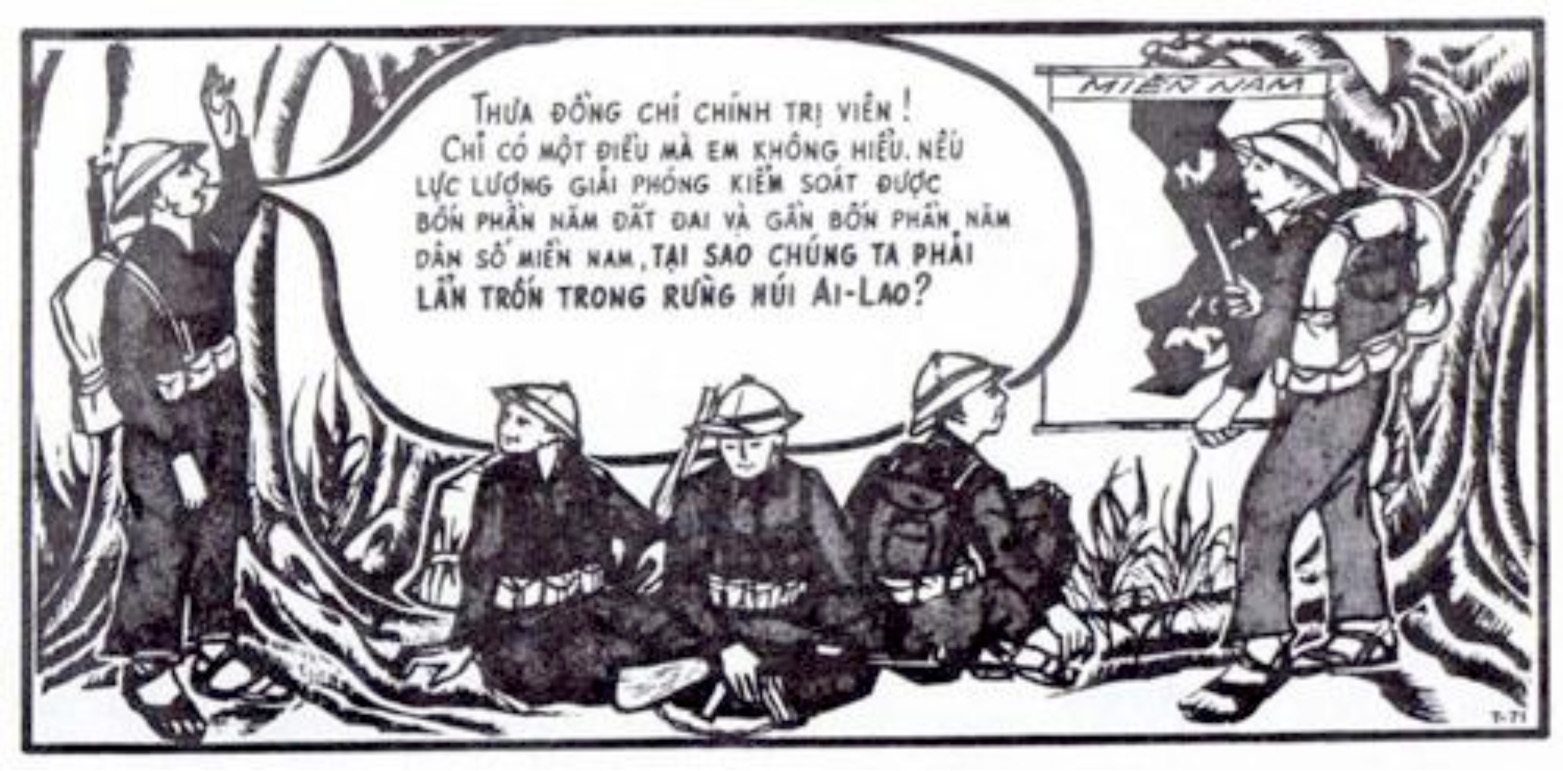

Leaflet T-71

The front of this leaflet depicts a cartoon of a North Vietnamese Army soldier questioning his unit political commissar. He asks:

Comrade Political Commissar. There is one thing I do not understand. If the liberation forces control four-fifths of the land and nearly four-fifths of the people in of the South, WHY DO WE HAVE TO HIDE IN THE JUNGLE AND MOUNTAINS OF LAOS?

Leaflets T-65, T-66, T-67 T-68, T-69 and T-70 all have Vietnamese text on the front and a Laotian safe conduct pass on the back that says:

Above is a Royal Lao Government Safe Conduct Pass. Present it to any soldier or government official. You will be warmly received.

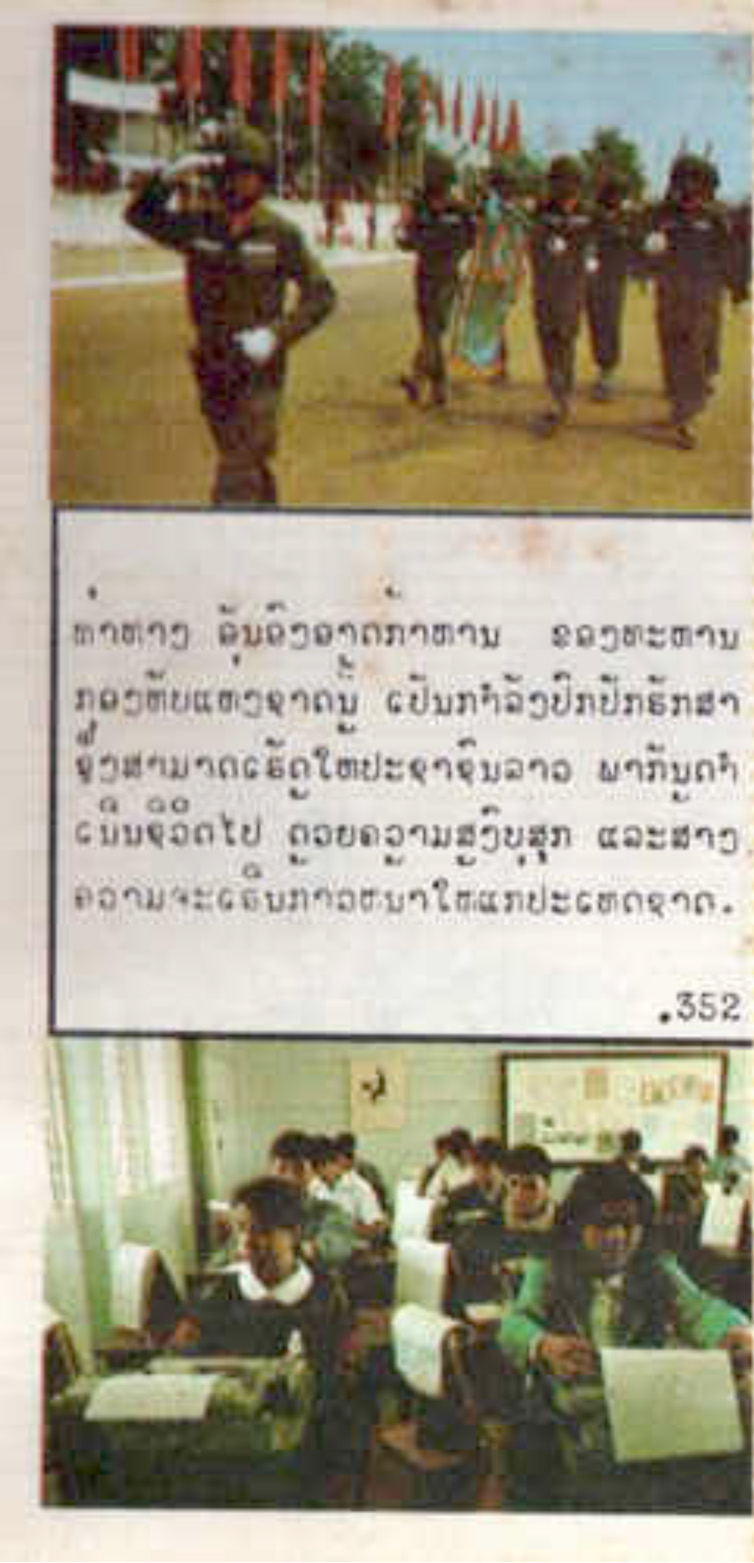

A 7th PSYOP Group 1972 Intelligence Special Report on Psychological Operations in Laos mentions a number of Royal Laotian Government and Pathet Lao programs. The report states:

The PSYOP objectives of the Royal Laotian Government are to reduce the combat efficiency of the enemy, to mold favorable attitudes toward the war effort, to stress the goodwill of the United States, to confuse the enemy concerning ideology and the aims of leaders, to convince enemy troops to defect, and to carry out plans for economic and other development while educating the people.

To carry out these goals the Government uses posters, leaflets, motion pictures, still pictures, cartoons, traveling theater groups PSYOP teams, loudspeaker programs, radio broadcasts, and printed media.

The Royal Lao Government has radio stations at Savannakhet, Pakse, Luang Prabang, Chimaimo, and Vientiane which transmit to an estimated 70,000 radio receivers in the country...The Lao publish Khao Phap Pacham Sapda, a weekly news and photo sheet that has a circulation of approximately 20,000 and reaches the largest number of illiterate people in the country.

Since most of the people are illiterate, radio and loudspeaker programs are the most effective from the standpoint of reaching numbers of people. The cartoons, plays, and to a lesser extent, leaflets are well received.

The report also mentions Pathet Lao psychological operations:

Pathet Lao themes are directed at youth, ethnic minorities, religious leaders, and government troops. Pathet Lao themes claim corruption and graft in the established government…The Pathet Lao direct the “war monger” theme to all sections of the society. Along with this is an anti-U.S. propaganda program designed for government troops. It stresses the righteousness of Pathet Lao programs and calls for the government troops to defect to the “rightful” side.

To carry out their objectives the Pathet Lao use radio, propaganda teams, motion pictures and printed media.

The U.S. military objectives for Laos were:

The withdrawal of all North Vietnamese troops followed by the re-establishment of the 1962 Geneva provisions. To accomplish this goal, US objectives were:

1) Maintain an outward appearance of strict neutrality for diplomatic reasons;

2) Maintain a relatively stable balance of political, military, and economic positions between the communist and the pro-US factions in Laos;

3) Maintain a friendly or at least neutral government on the borders of Thailand;

4) Achieve maximum attrition and disruption of North Vietnamese logistics flow through the use of air power.

Our aircraft will continuously attack…

One of the most interesting Lao government leaflets depicts their aircraft attacking porters and soldiers bringing supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Text on the front is:

Our aircraft will continuously attack the people who aid the Viet Cong

The back of the leaflet bears a long threatening message that is written poorly, using a mix of Lao, Pathet Lao and Thai words. It says in part:

To the Heads of the villages in Viet Cong controlled areas,

We are deeply concerned with the peace and freedom of Lao people…But, many of the Lao people are living very dangerously and close to tragedy. You are still supporting and cooperating with our enemy, the North Vietnamese. Therefore, we want to reason with you in good faith. We need you to face the truth. We want you to understand the danger of helping the North Vietnamese. If the Lao people in these areas continue to support the Viet Cong, helps and cooperates with them, the only choice we have is to use our weapons and guns and bombs continuously to destroy the enemy.

Therefore, we warn everyone that we are dropping bombs that can destroy every living thing. We warn all citizens against riding in boats, riding motor cycles, bicycles and helping the enemy by supplying tools and repairing the roads used by the Viet Cong. We want you to understand that continued aid to our enemy will mean that the people living in the controlled areas will be targeted and bombed until nothing is left.

Kenneth Conboy, author of Shadow War: The CIA’s Secret War in Laos told me:

The leaflet operations by the Royal Lao government were somewhat limited, which reflected the limited extent of territorial control by that country's government for most of the war. They did some leaflet drops, but faced serious problems because the Royal Lao Air Force was propeller driver (read: slow) and they were running up against some very competent anti-aircraft coverage. Most of the Royal Lao Government leaflets I have seen have depictions of the King and apparently tried to feed off Lao loyalty to the throne. They also did some “white” radio operations. And, on one occasion, they feted a Pathet Lao battalion that defected to the government. Calendars and posters were printed up and widely distributed to mark the occasion.

By contrast, the psywar efforts of the U.S.-backed irregular forces were far more extensive. Relatively powerful radio stations were operated out of both Long Tieng and an airfield called PS 44 in the south. Some of these were “gray,” the most prominent being the Union of Lao Races station. Both outposts also ran a number of black stations. Leaflets were also designed at these outposts, but the irregular forces ran up against the same anti-aircraft issues that were faced the Royal forces. Tellingly, many of these leaflets offered rewards for pilots shot down previously.

Prior to 1965, the Directorate of National Coordination had responsibility for psywar; though I don't think they actually performed this function. The DNC was disbanded in 1965 following a coup that saw its leaders go into exile. Colonel Khamthene Chinyavong is the full name of the PSYOP officer who was in Vientiane near the end of the war. Brigadier General Etam Singvongsa was the overall Commander of PSYWAR. He has since passed away in Australia.

A CIA Surrender Pass for Laos

Speaking of Long Tieng, Captain Bob Farmer was one of the covert American pilots. In six months in 1966, Captain Farmer flew combat missions using the call sign “Butterfly.” The aircraft most often used by Butterfly Forward Air Controllers was the PC6A Pilatus Porter, flown by both Air America and Continental Air Service. Officially, no US combatants were in neutral Laos in accordance with the 1962 Geneva Accords, so officially, the Butterflies did not exist.

Farmer found hundreds of forgotten safe conduct passes in the CIA storeroom at Long Tieng Air base. He started taking them on strike missions and throwing them out the aircraft window when he had the opportunity. They measured 6.5-inches x 9-inches and depicted the flag of Laos in bright red color.

Most of the Laos leaflets are standard 3-inch x 6-inch black and white rotators. Other are full color on the front and black and white on the back and larger at 2 3/4-inch by 8 1/2-inch. All of the leaflets in the Lao language have code numbers starting with a period like “.23” or “.335.” Many of the leaflets are in Lao on one side and Vietnamese on the other since they were aimed at both the Pathet Lao and Vietnamese fighting in Laos. Finally, some of the leaflets are exactly the same and found in both Vietnamese and Lao. So, there are many possible combinations. I have selected some leaflets that I found particularly interesting, either because of the message or the image. I have made no attempt to write a detailed in-depth report. This is just a light look at American PSYOP in Laos where I hope to show and discuss perhaps a dozen or so different leaflets.

We should mention that the codename for PSYOP booklets in Laos and Cambodia was “Soap Chips.”

The Allies studied the Pathet Lao reaction to American PSYOP in an August 1972 report entitled “Pathet Lao Reaction to American PSYOP.” The five-page document listed a number of Communist broadcasts that mention U.S. psychological operations. Some of the broadcasts quoted were:

On 22 August, Radio Pathet Lao carried a long (6 minutes) broadcast entitled “Effectively Promote Security Tasks in Various Area to Smash Enemy PSYWAR Activities Intended to Create Confusion Among Our People.” Radio Pathet Lao said that U.S. and Royal Lao PSYWAR included clandestine radio stations, utilizing all available propaganda tactics…And sending bandits and commandoes to create unrest.

On 26, August Radio Pathet Lao carried a seven-minute broadcast to the people of Laos entitled, “The PSYWAR Tactics of the U.S. Imperialists Can Deceive No One.”

On 7 September, Radio Pathet Lao carried an eight-minute broadcast entitled, “Maintaining Security and Countering U.S. Psychological Warfare is an Important and Urgent Task Which Must be Implemented by our People.”

On 11 September, Radio Pathet Lao carried a five-minute program entitled, “What is Psychological Warfare?” Radio Pathet Lao discussed the U.S. schemes of carrying out PSYWAR tactics to thwart the Lao revolutionary struggle.

All of this data illustrates two very interesting points. U.S. Intelligence was clearly monitoring the Communist radio and taking note of everything said. At the same time, it seems clear U.S. psychological operations were having their effect on the Communists and forcing them to constantly attempt to counter it by indoctrinating the people against PSYOP in the areas that they occupied.

The civilian "Bible" of Vietnam War PSYOP is the Robert W. Chandler book War of Ideas: The U.S. Propaganda Campaign in Vietnam, A Westview Special Study, Boulder, CO, 1981. According to Chandler, during its seven years in Vietnam, the United States Information Agency (USIA), supported by the armed forces, littered the countryside of the North, South, and the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and Cambodia with nearly 50 billion leaflets – more than 1,500 for every person in North and South Vietnam.

Other books which one supposes would mention psychological warfare do not. There is no mention of PSYOP over Laos in Stanley Sandler’s Cease Resistance – it's Good for You: a History of the U.S. Army Combat Psychological Operations, or in Christopher Robbin’s The Ravens. The latter book is the history of the secret war fought in the air and one would expect numerous examples of psychological operations.

There are some rare comments concerning leaflet campaigns in the various histories of Civil Air Transport (CAT), later renamed Air America, and often called the “CIA airline.” I note that in late 1955 three CAT C-46s air-dropped rice bags and propaganda leaflets along the Lao-China border and the Lao-North Vietnam border. In December 1971, after an aircraft was lost, Air America aircraft dropped reward leaflets for information on the plane and crew.

Leaflets to Laos are fairly rare. Unlike Vietnam where about three million Americans slogged through the swamp and bush, a very limited number of Americans were in Laos. Not only that, but the war was a secret one and the Americans were not encouraged to bring back souvenirs. Stories about that war are endless. These will sound like tall tales and maybe they are…and you never heard them from me.

A friend from the 101st Airborne claims to have made two combat jumps into Laos. He is unable to wear the star over his jump wings because the jumps do not exist.

I had a soldier ready to retire who had spent some time in Laos. We had a very difficult time proving his “twenty good years” since his records had a gaping hole in them. I thought his pay records would clear everything up but he told me he was paid by an officer out of a brown paper bag. I was sure that was a lie because the military is very careful about paperwork. Years later when I was at CIA Headquarters in Langley I met an Air Force general, a youthful-looking very fit guy with a crew cut. He was introduced as the paymaster for some of the Laos operations…out of a brown paper bag.

Discussing Laos more recently, a veteran told me that before a flight a mail clerk dropped off some copies of the Stars and Stripes in the briefing room. He stuffed one in his helmet bag on the way out the door. He then flew to Khe Sanh, where he picked up an ARVN General and flew him to a firebase in Laos. While waiting for the general to finish his briefing he took the newspaper out of his helmet bag and the headline was, “NIXON: NO U.S. TROOPS ON THE GROUND IN LAOS.” He says he looked around and thought, “Well, if I'm not in Laos, where the fook am I?”

Time magazine of 22 February 1971 seems confused. It says:

Reporters also saw some American bodies being brought back from Laos. Was someone fudging on the congressional curbs on the use of ground troops outside South Vietnam? White House Press Secretary Ron Zeigler insisted that the reports probably involved Special Forces intelligence teams that have operated in Laos for years. Still, the impression remained that some American advisors had crossed the border.

In fact, on 8 February 1971, 20,000 South Vietnamese troops crossed the border into Laos on a major incursion known as Lam Son 719. The operation was named in honor of the Vietnamese Emperor Le Loi who was born in the village of Lam Son. American ground forces were not supposed to be in Laos, but the Air Force supplied fighters, bombers and attack helicopters to support the Vietnamese troops. The ARVN were fiercely attacked by an estimated 36,000 North Vietnamese troops with as many as five divisions, tanks and heavy artillery. On 9 March 1971 the assault force was withdrawn. The North Vietnamese lost over 20,000 troops, South Vietnamese suffered about 9,000 casualties, the U.S. about 1,462 casualties. 108 U.S. helicopters were lost and another 618 were damaged.

This battle was lost before it began because the North Vietnamese had so infiltrated the Government of South Vietnam that they knew of the attack months before it occurred. Larry Berman mentions Lam Son in Perfect Spy, Smithsonian Books, 2007. This is the biography of North Vietnamese spy and Time Magazine correspondent General Xuan Pham An. He says in part:

Everyone knew about Laos well in advance, except those in charge…Northern spies were everywhere in the south, from the hootch maids cleaning up after the G.I.s, to the ranks of the ARVN, to the Saigon press corps – and it would be later reported, even inside the Da Nang headquarters of I Corps where Operation Lam Son 719 was long planned…The Communists knew of it maybe six months in advance.

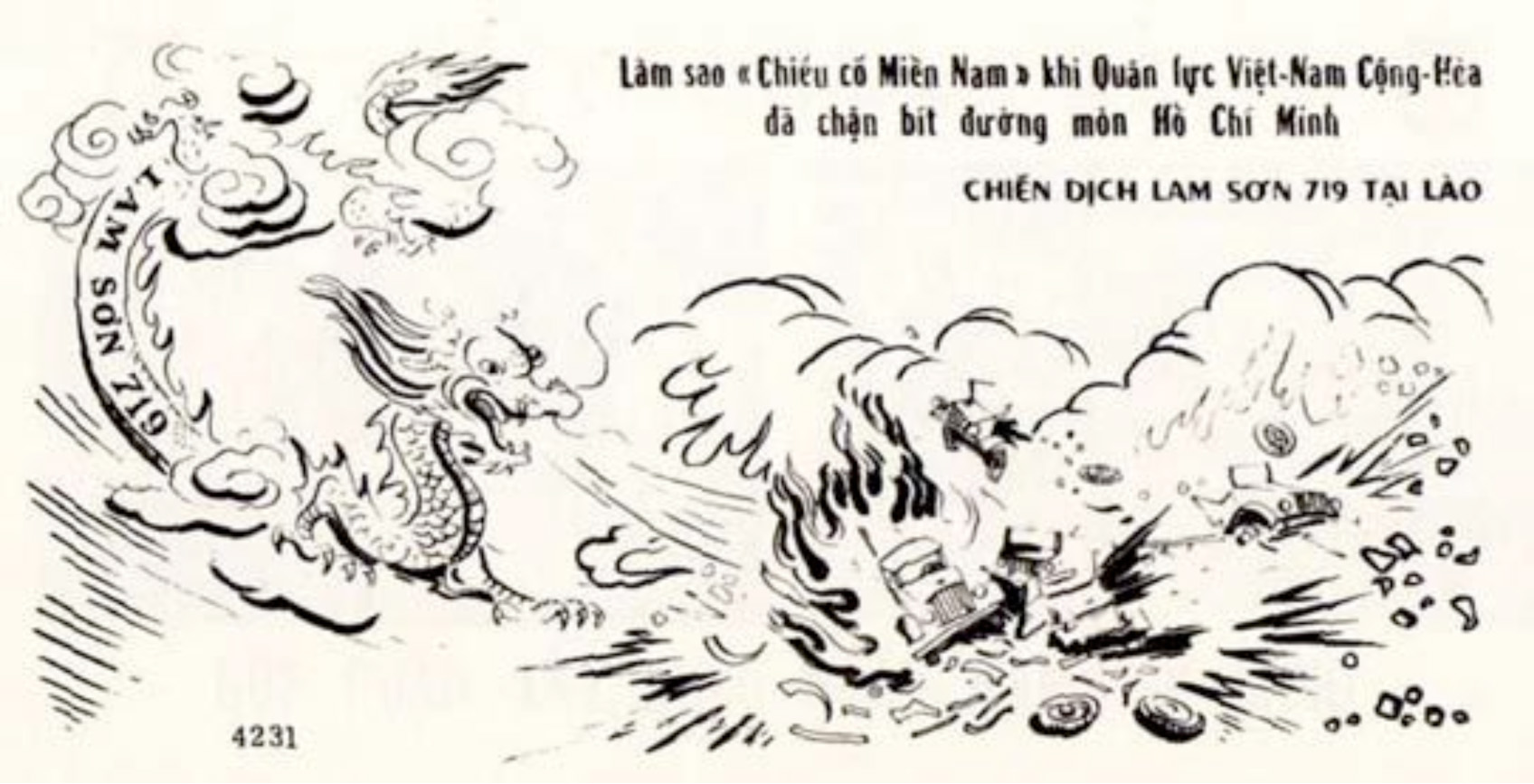

Leaflet 4231

Lam Son Leaflet 4231 depicts a dragon swooping down on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and destroying trucks by fire. The text is:

The Party cannot “Liberate the South” because the forces of the Republic of Vietnam Have blocked the trail.

The back is all text:

Liberation of the South

This is what the Party keeps telling you again and again. It cannot be done. The armed forces of the Republic of Vietnam are attacking the Ho Chi Minh Trail on which you must travel in force. You will very likely be sacrificed on the Trail. Return home now to your family or report to the Army of South Vietnam or the Royal Laotian Government forces.

We should mention that there were numerous deception operations involved in this incursion. John B. Dwyer mentions one in Seaborne Deception, the History of the U.S. Navy Beach Jumpers.

During Operation Lam Son 19 (the Multidivisional incursion into the Laotian Panhandle) SOG carried out diversionary insertions at four bogus landing zones and conducted simulated parachute raider and actual resupply bundle insertions at eight phone drop zones…

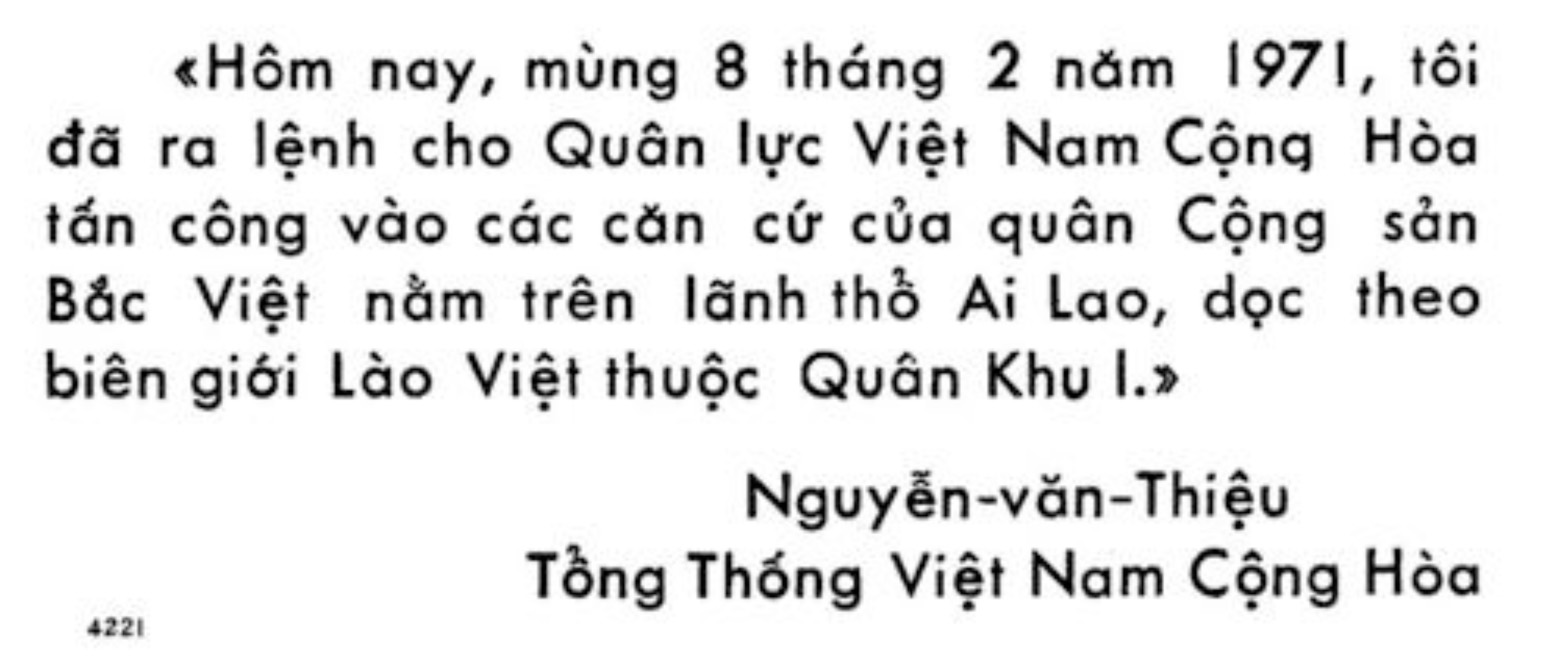

Leaflet 4221

I normally do not depict leaflets that are all text but this one is interesting because it is signed by President Thieu. We who lived through that era recall the parade of leaders that came forward as America searched for a charismatic man that could motivate the people to come together and lead the fight against the Communists. There was Ngo Dinh Diem and his wife, “the Dragon Lady,” and General Duong Van “Big” Minh, Nguyen Van Thieu, and my personal favorite, the gallant airman, General Nguyen Cao Ky. They all attempted to take power and lead the nation, and ultimately, they all were unsuccessful. The text on this leaflet is in part:

Today, 8 February 1971, I have ordered the Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam to attack the Communist North Vietnamese bases on Laotian territory along the Vietnam – Laos border in Military Region I.

Nguyen Van Thieu

President of the Republic of Vietnam

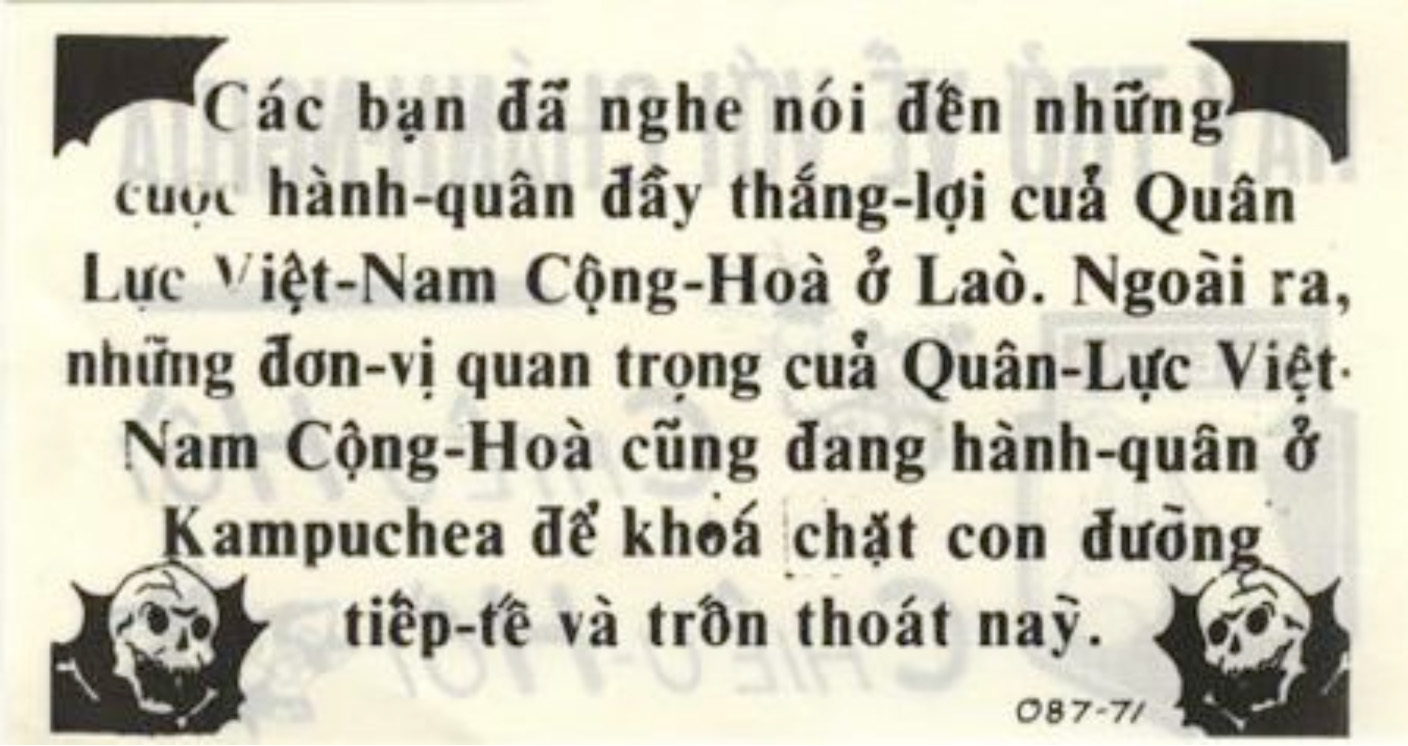

Australian Leaflet ATF-087-71

The Australian 1st Psychological Operations Unit also produced leaflets that mention the fact that the Allies are operating in Laos and Cambodia. The threat is that if the Ho Chi Minh Trail can be cut off, then the Communist units will become vulnerable due to a lack of weapons and ammunition. The Australians printed about 50,000 of these leaflets on 23 February 1971 and disseminated them by aircraft. The Chieu Hoi symbol is on the front with the text:

Rally to the Cause - CHIEU HOI - CHIEU HOI

The back depicts two grinning skulls and the text:

You have heard of the successful Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces operations in Laos. Large Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces units are also operating in Cambodia to close this supply and escape route.

Before we start to illustrate the leaflets I should point out that there were many American leaflets dropped on the Vietnamese troops and supply system in Laos. We will depict a few, and the reader will find many more in my article about the PSYOP campaign over the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In general, for the purposes of this article we will mainly show leaflets printed in the Lao language for the Lao.

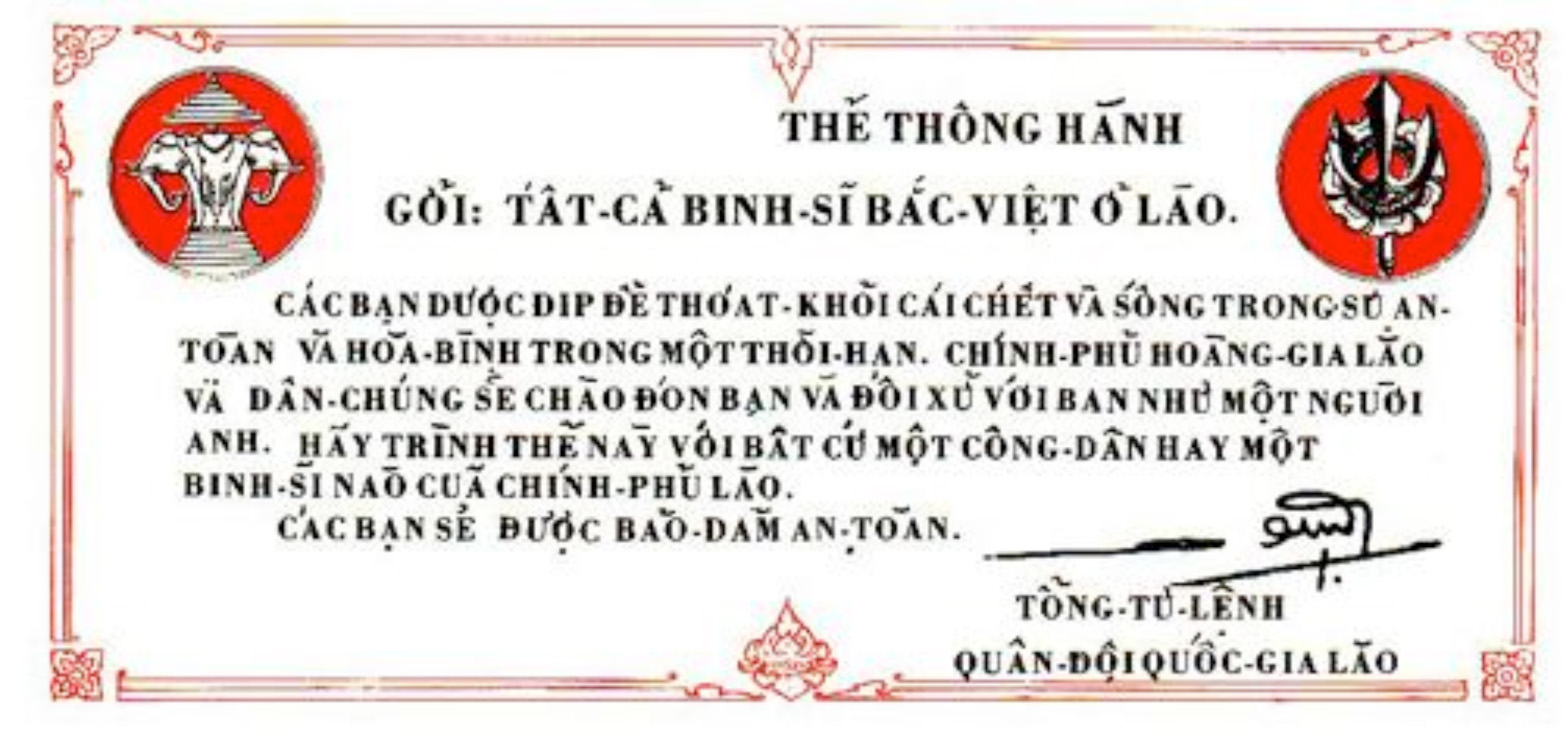

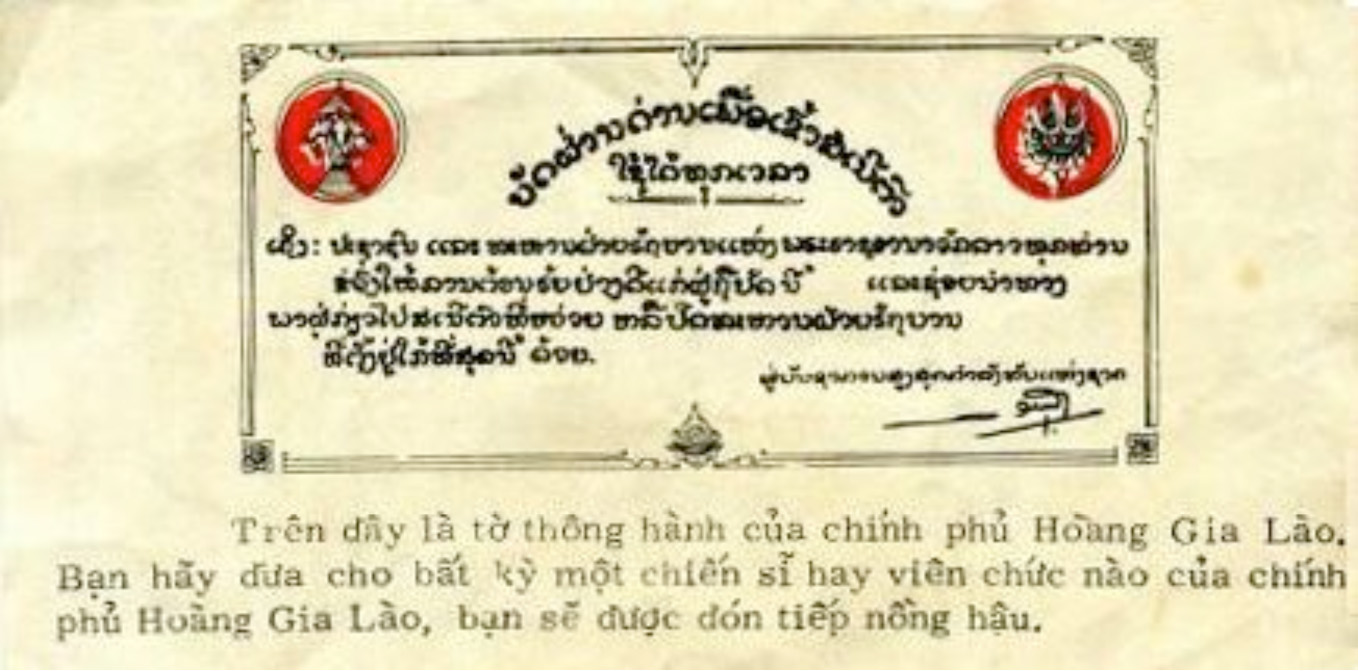

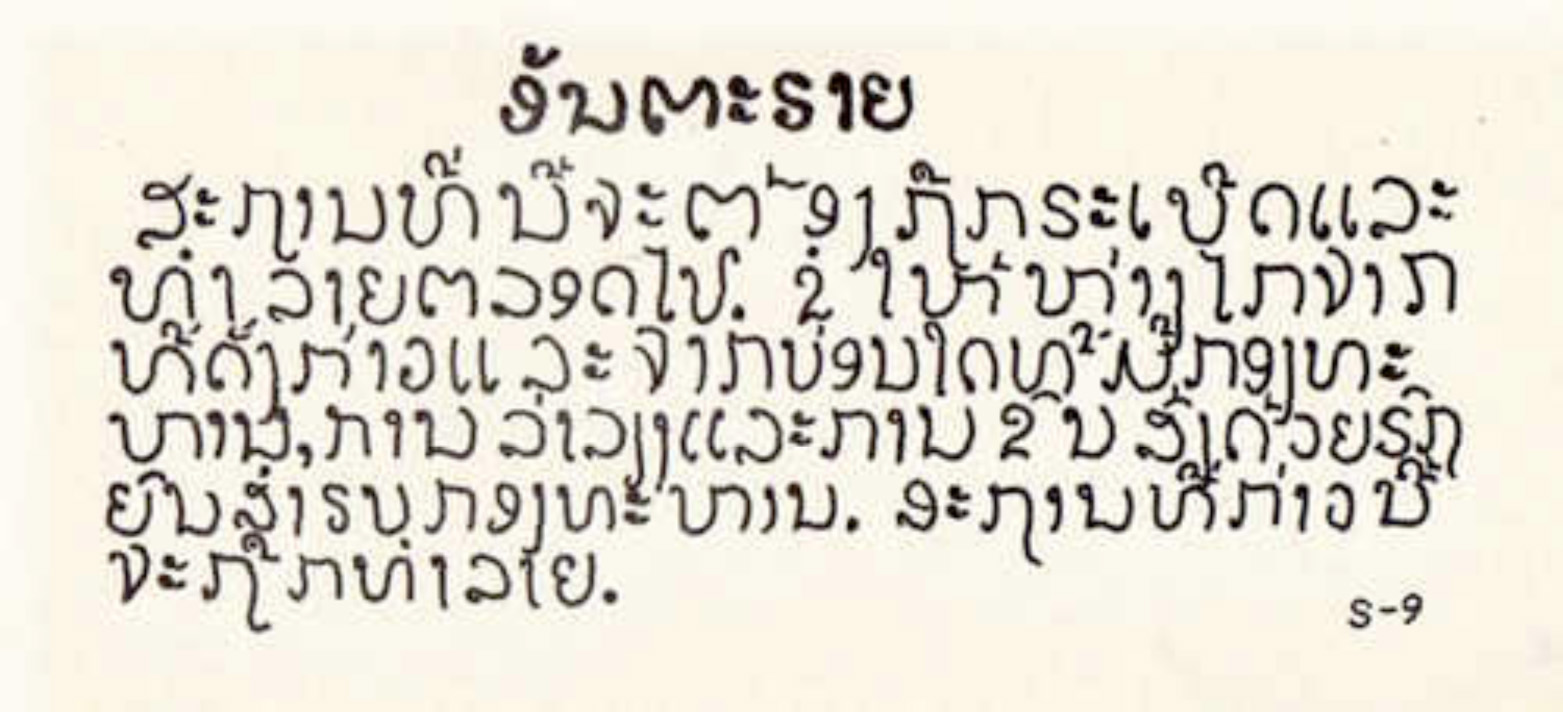

Safe Conduct Passes

A great number of the leaflets dropped over Laos bore a safe conduct pass. In fact, many of the leaflets to the Vietnamese troops had a safe conduct pass on the back and told the Vietnamese how they could use it to surrender to government forces. There are probably more leaflets bearing some form of safe conduct pass than any other theme.

Ho Chi Minh Trail Campaign Leaflet T-16

I chose this leaflet because it bears the symbol of Laos. This is the three-headed Erawan elephant national symbol from Hindu mythology of the 14th century kingdom whose name translates to “Land of the Million Elephants and the White Parasol.” This Lao image is the most popular theme among the Trail leaflets and there are over a dozen different types with various surrender messages. The United States had to deal with the Lao government to arrange for them to accept Vietnamese prisoners. All of these leaflets bear text in Vietnamese on one side and Lao on the other. The Vietnamese-language side of the leaflet says:

Pass for safe conduct

To: All North Vietnamese Soldiers in Laos.

You are offered the chance to escape death and live in safety and peace for the duration. The Royal Lao Government and people will welcome you and treat you as a brother.

Show this pass to any Royal Laos Government citizen or soldier and he will guide you to safety.

Commander in Chief

Lao National Armed Forces

The Lao-language side says:

Pass for Safe Conduct – Valid at all times

To: All Citizens and Soldiers of the Royal Laotian Government.

Please welcome the bearer of this pass and provide him with safe conduct to the nearest Royal Lao Government unit or post.

Commander in Chief

Lao National Armed Forces.

Leaflet T-66

The front of trail leaflet 66 depicts a Laotian safe conduct pass and the text:

Above is a Royal Lao Government Safe Conduct Pass. Present it to any soldier or Government official. You will be warmly received.

The back is all text and says in part:

ALL NORTH VIETNAMESE ARMY AND FREE WORLD SHOULD

BE WITHDRAWN FROM SOUTH VIETNAM

Your leaders, who are living comfortably in Hanoi while you suffer in the jungles of Laos, claim you are participating in war to liberate the South from foreign aggressors. Don’t be fooled by this. The free world allies of the Republic of Vietnam sent combat forces into South Vietnam at the request of the Government of Vietnam only after attacks had been launched there by regular units of the Army of North Vietnam…

There are a tremendous number of leaflets dropped over Laos with a threatening message to the Vietnamese on one side and a Laos safe conduct pass on the other. An example is T-2-5TC which tells the Viet Cong not to sacrifice their lives needlessly on the front and depicts the Lao safe conduct pass on the back with a recommendation that the finder take the leaflet to a representative of the Vientiane government.

Reward Leaflets

The Allies dropped 98,336,000 leaflets over South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in 1971 to advertise the rewards program. The reward operations leaflet program during 1971 and 1972 were Operations Brown Stallion, Buffalo Track, and Elephant Walk. American PSYOP specialists printed the leaflets in Lao, Vietnamese and Cambodian with “pointee-talkee” pictures for the illiterates. They dropped another 32,200,000 reward leaflets in early 1972. The following monetary rewards were authorized to indigenous civilians: $5,000 for returning US personnel, $500 for information leading to the return of US personnel, $400 for return of a body to friendly forces, and $150 for authentic information of status or location.

A highly classified undated document that was declassified on 23 Jul 1986 mentions what appears to be the first reward leaflets dropped on Laos. Some of the text is:

Assume Vientiane is aware that embassy has approved five reward leaflets on U.S. prisoners of war in Laos which developed jointly by embassy and Joint Personnel Recovery Center...

MACV has been dropping reward leaflets South Vietnam and Cambodia for about two years but not Laos. Reward program provides for compensation in following U.S. dollars or equivalents thereof in foreign currencies.

- For returning a U.S. missing person to friendly control: Laos $2,000 – All other locations $5,000.

- For providing information leading to recovery of missing U.S. personnel by friendly forces: Laos $250 – All other locations $500…

Rewards paid from 1967 to present - $12,149

Number of leaflets dropped in South Vietnam and Cambodia – 28 million every 6 months.

The CINCPAC Measurement of Progress in Southeast Asia dated 31 December 1967 shows that leaflets dropped in Laos during the year 1967 were over 10 million in every month except June and over 20 million in the last four months of the year. The report states that leaflets dropped in Laos in 1967 were 33 percent higher than were dropped in 1966.

During the Vietnam War, American soldiers and airmen were often in danger in the nations bordering Vietnam as their missions called for them to overtly or covertly cross the borders into the “neutral” countries to attack or pursue the NVA units hiding in the jungle, or the supply columns coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

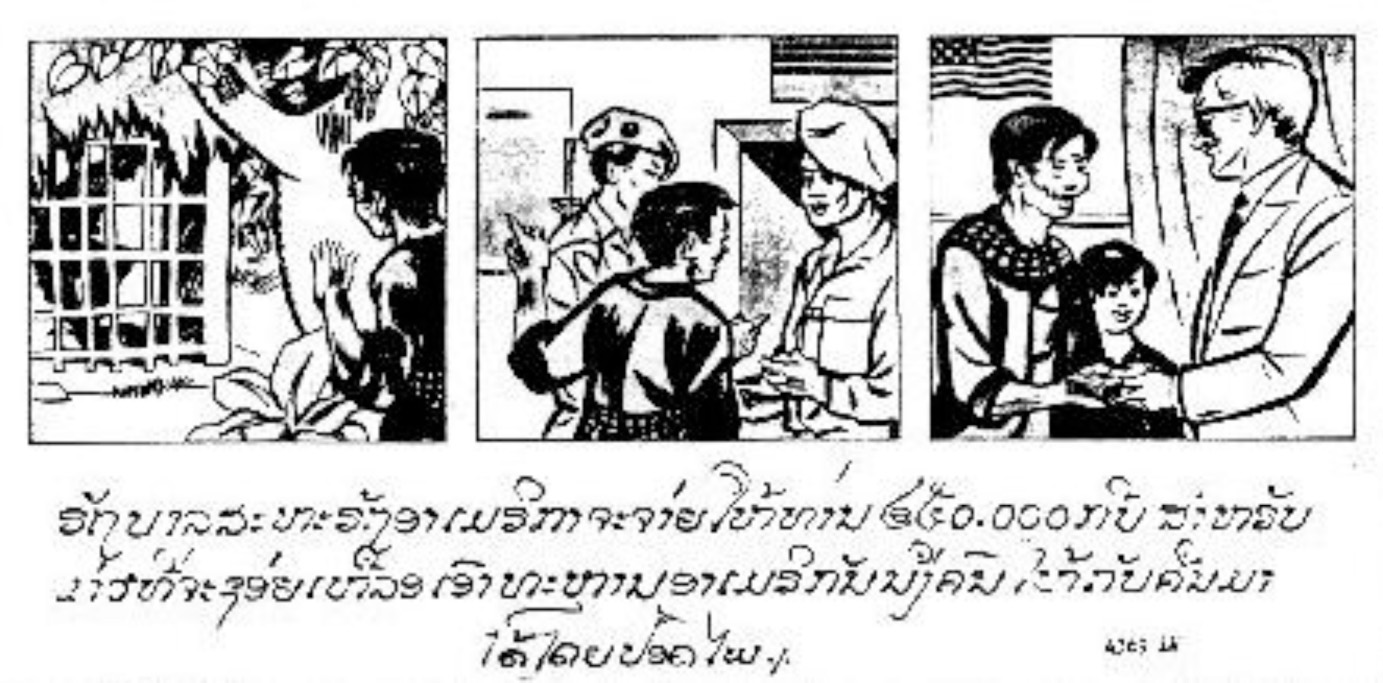

One series of leaflets depict the same 3 cartoons on the front and back. In each, a local sees an American in a cage, tells the local military, and at the end receives a reward from a Caucasian in a suit and tie. The text is identical on the front and back of all of the leaflets:

The United States Government will pay you $500 for information leading to the safe rescue of a U.S. serviceman.

Leaflet 4369LV

Leaflet 4369CV has the text in Vietnamese on one side and Cambodian on the other. Leaflet 4369LC is identical except that the languages are Lao and Cambodian. Leaflet 4369LV is in Lao and Vietnamese. Leaflet 4369V has the cartoon and text in Vietnamese on the front and the back has a picture of a $500 bill.

Leaflet 4370CV

A second series has the same theme, but with slightly changed pictures and text. Leaflet 4370CV has four cartoon boxes. A local farmer sees an American serviceman walking in the woods. He guides the American back across the border to Vietnam. The American shakes hands with a Republic of Vietnam soldier. In the last box, the farmer receives a reward from an American in a suit. The text is almost identical to 4369 except that the reward is multiplied 10 times:

The United States Government will pay you $5000 for information leading to the safe rescue of a U.S. serviceman.

The text is in Cambodian and Vietnamese. Once again, the LC version has Lao and Cambodian text, the LV version has Lao and Vietnamese, and the final V version in Vietnamese and depicts a picture of a $5000 bill.

The United States prepared a number of propaganda leaflets to the Pathet Lao and Lao civilians depicting Royal Lao currency and offering rewards for the return of American and Lao pilots. The leaflets were mostly black and white but often had a touch of red where the symbol of Laos was depicted and rewards were mentioned. The notes were prepared in two sizes, standard 3 x 6-inch leaflets and 6.29 x 11-inch handouts.

Leaflet .110 (front)

Standard leaflet .110 (the larger size is coded .111) depicts a stack of 1000 kip banknotes with Lao three-headed Erawan elephant national symbols from Hindu mythology at the left and the right. The national symbol comes from the 14th century Lao kingdom whose name translates to “Land of the Million Elephants and the White Parasol.” The text is:

With wealth you can make wonderful things.

For information on Royal Laotian or U.S. prisoners of war or for assisting Royal Laotian Air Force or U.S. pilots back to the government.

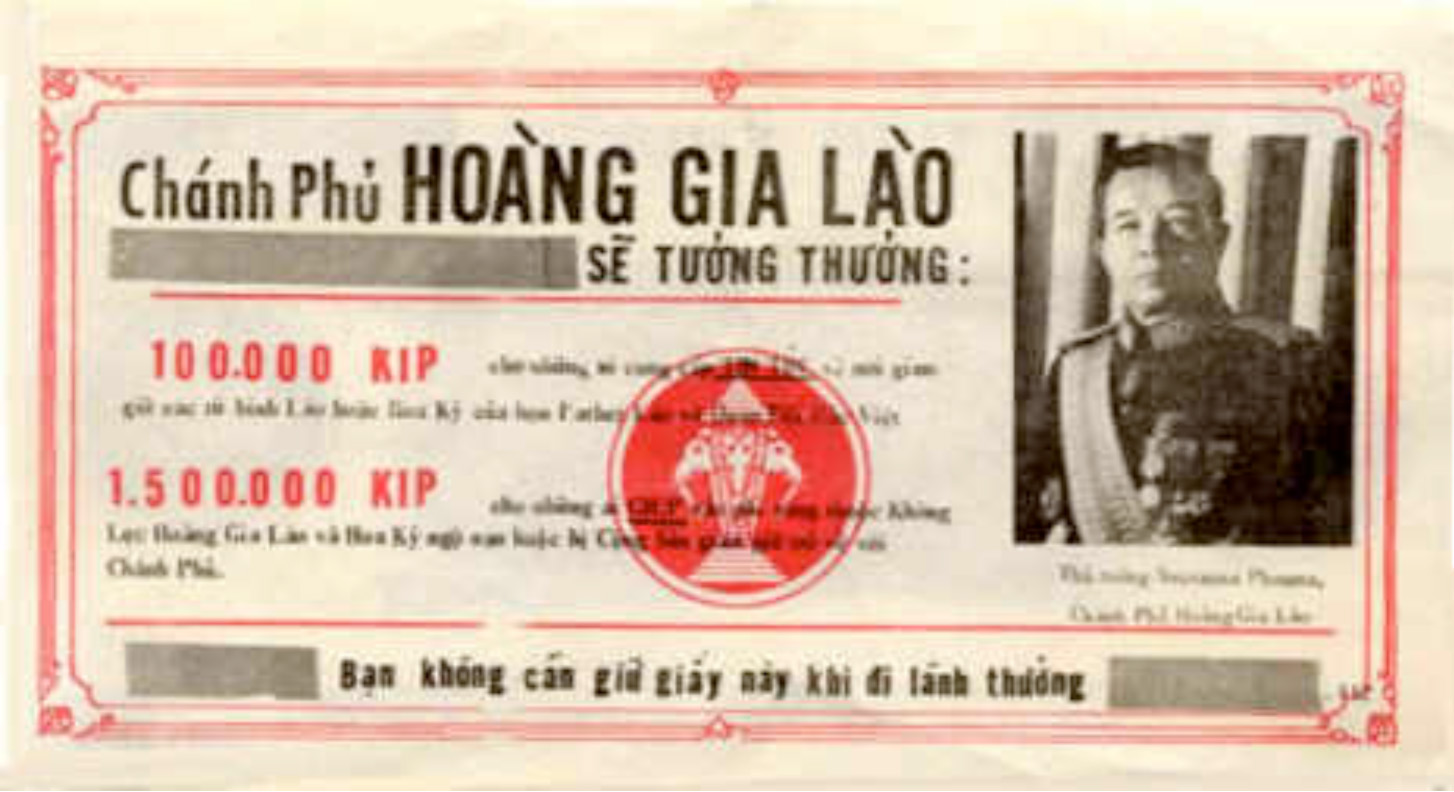

Leaflet .110 (back)

Souvanna Phouma is depicted on the back. The text is:

Souvanna Phouma, Prime Minister, Royal Lao Government.

The Royal Lao Government promises to pay you:

100,000 kip for information on the location of Royal Lao Government or U.S. prisoners held by the Pathet Lao or North Vietnamese Army.

1,500,000 kip for assistance to Royal Lao or U.S. pilots returning to the government.

You need not keep this paper to collect the reward.

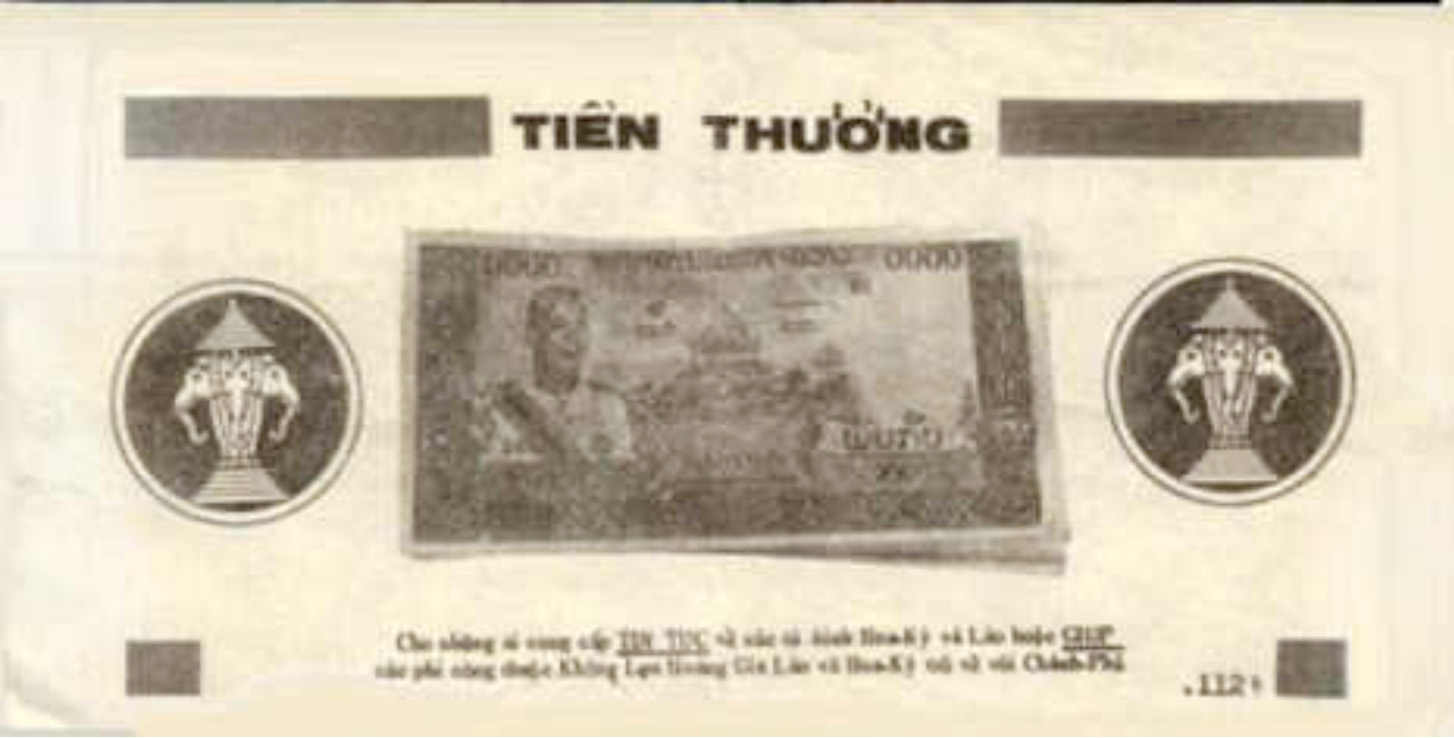

Standard leaflet .112 (larger size is coded .113) depicts a stack of 1000 kip banknotes with Laotian three-headed Erawan elephant symbols from Hindu mythology at the left and the right. The text is:

Reward.

A cash reward will be given to those who provide information concerning U.S. and Laotian prisoners, or who assist Royal Laotian and U.S. pilots in returning to the government.

Souvanna Phouma is depicted on the back. The text is:

Souvanna Phouma, Prime Minister, Royal Lao Government.

The Royal Lao Government will give a reward of:

100,000 kip to those who provide information concerning U.S. or Laotian prisoners of the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese Army.

1,500,000 kip to those who help Royal Laotian and U.S. pilots who are downed or being detained by the Communists to return to the government.

You need not keep this paper to collect the reward.

Leaflet .112 (front)

Standard leaflet .112 (larger size is coded .113) depicts a stack of 1000 kip banknotes with Lao three-headed Erawan elephant symbols from Hindu mythology at the left and the right. The text is:

Reward.

A cash reward will be given to those who provide information concerning U.S. and Laotian prisoners, or who assist Royal Laotian and U.S. pilots in returning to the government.

Leaflet .112 (back)

Souvanna Phouma is depicted on the back. The text is:

Souvanna Phouma, Prime Minister, Royal Lao Government.

The Royal Lao Government will give a reward of:

100,000 kip to those who provide information concerning U.S. or Laotian prisoners of the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese Army.

1,500,000 kip to those who help Royal Laotian and U.S. pilots who are downed or being detained by the Communists to return to the government.

You need not keep this paper to collect the reward.

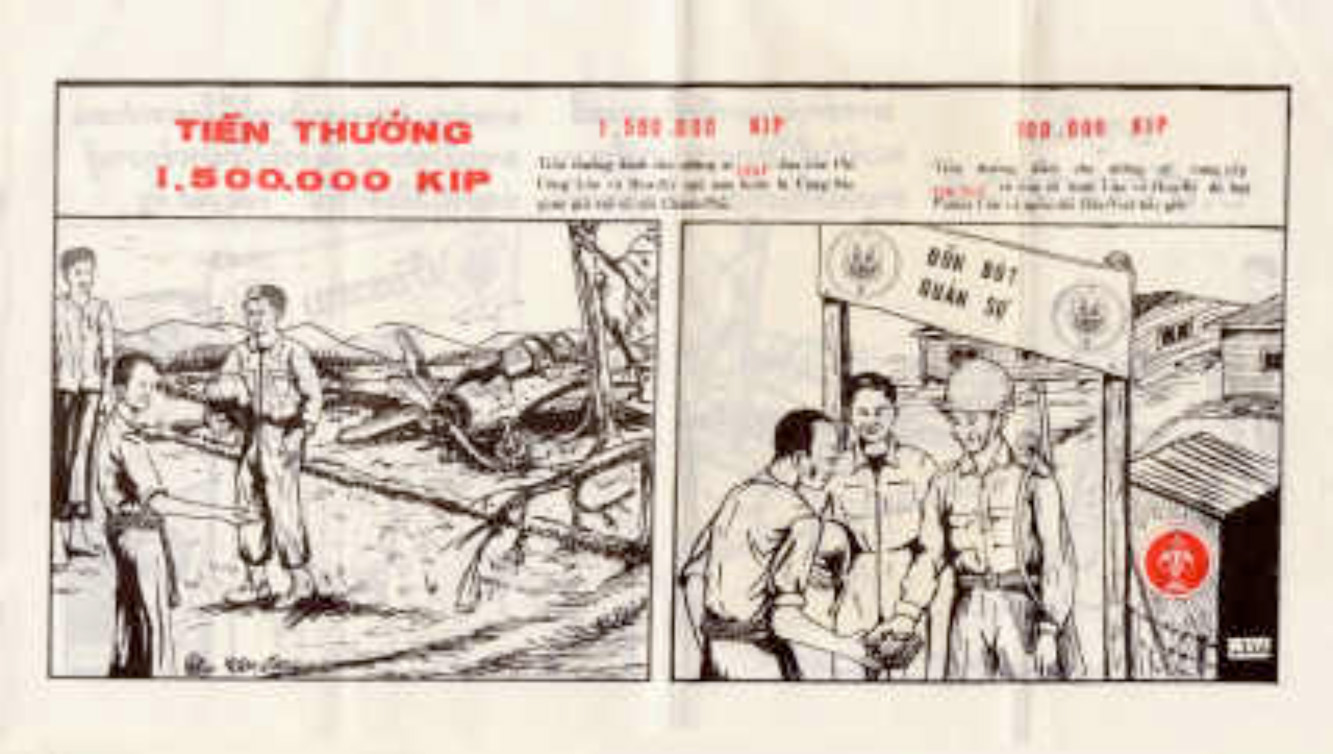

Leaflet .114

U.S. reward leaflet .114 for Laos is made up of two identical cartoons that appear on both the front and back. The only difference is that the text on one side is written in Vietnamese, the other side in Lao.

The first illustration (at left) depicts a downed Allied pilot meeting villagers. The second illustration (at right) depicts the pilot and a friendly villager meeting a government officer who rewards the villager with a cash payment.

The text at top is:

1,500,000 kip: A cash reward to those who help Royal Laotian and U.S. pilots who are downed or being detained by the Communists to return to the government.

100,000 Kip: A cash reward to those who provide information concerning U.S. or Laotian prisoners captured by the Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese Army.

Banknote Leaflets

Pathet Lao 200 Kip Propaganda Banknote

The Pathet Lao had a set of banknotes ready for issue after they had “liberated” all of Laos. With the rampant inflation caused by the Allied dropping of their captured banknotes, they decided to exchange a reasonable amount of notes for each person for the new banknotes. These banknotes are found in denominations of 10 and 20 dong, and 50, 100, 200 and 500 kip. The 200 Kip depicts soldiers and transportation of war material on the front. The back shows a textile factory and the That Luang Temple. The genuine 200 Kip note is handsomely produced, deep green in color with serial numbers at the lower left and right front side in red.

Shortly after these notes appeared, a similar note was found printed just a shade lighter green and without serial number. What made this new note especially interesting was that on the back, in place of Lao Temple, a portrait of Ho Chi Minh was substituted. When these notes first appeared, it was believed that they were genuine Pathet Lao notes. Another story surfaced in 1977 when the Bangkok Post headlined a short article “Ho banknotes were faked.” The story explained:

The Laotian 200 kip note bearing a portrait of the late Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh that was published in the Bangkok Post of June 16th was actually counterfeited by the former Vientiane government to mislead the people in the liberated areas, Mr. Kach Kitthavong, Charge d'Affaires of the Laotian Embassy, said yesterday.

The Royal Lao government printed these notes in an attempt to convince the Pathet Lao that they were fighting for Vietnam and not for their own cause. It is reasonable to assume that the Lao people might have reacted negatively to a Vietnamese leader prominently placed on their revolutionary currency.

These notes caused a great amount of damage to the image of the Pathet Lao political and military forces in the eyes of the Lao people. A tremendous uproar ensued within the ranks of the Pathet Lao and their North Vietnamese advisors. All military units were tasked to recover the propaganda banknotes immediately after a drop was reported, and, as a result, these notes are extremely rare.

Persistent rumors have identified the CIA as the originator of this parody, although the report mentioned above placed responsibility with the Ex-Royal-Lao government. Possibly both parties collaborated. In a March 1992 Public Broadcasting System Nova program, “Making a dishonest buck,” William Wofford, a pilot of Air America, the unofficial CIA airline, displayed two notes that he dropped in 1970 on the Laotian city of Xam Nua (Samneua), where, in limestone caverns, the Pathet Lao housed their national headquarters, a munitions factory, and a cadre training school. Nova asserted that the notes were probably of CIA origin. One of these notes was the 200 kip parody with Ho Chi Minh. Wofford told me later that he flew one such currency flight about 1969-1970, which originated in the CIA's super secret Long Tieng base. The complex, designated Lima Site (for Laos) was known as LS-20A. The pilots routinely alluded to it as “Twenty alternate.” The currency drop occurred on the way back from a regular mission over northern Laos. Wofford flew a DeHaviland DHC-4, designated by the USAF as the C7A Caribou, a two-engine propeller-driven utility transport capable of a 7000-pound payload.

Leaflet .31

I am going to place leaflet .31 here because it shows the exact same banknote that the Lao government parodied. The front of the leaflet depicts the back of the Pathet Lao 200 Kip Propaganda Banknote in black and white with the propaganda text diagonally:

This currency is counterfeit and has no value – it cannot be used

The back is all text:

The communists have printed this fake currency. This currency has no value at all.

It cannot be used in exchange for other currency.

The communists force people to distribute the fake currency for them.

People who are not educated and don’t know the rules of law and are asked to deliver the currency. The government warns, “Do not accept it or be tricked by the communists.”

Anyone who receives or is asked to distribute the currency should notify the local Police Chief.

The whole Lao citizenry hates the fake money and the communists who print and distribute the fake money. The next generation will inherit the problem. [If the economy is destroyed because of the distribution of counterfeit currency].

The Royal Kingdom of Laos National Military

There is reason to believe that many of these leaflets were dropped as part of an “Operation Fountain Pen.” The report Quantitative Analysis of Operation Fountain Pen implies that this secret operation commenced on 10 May 1969. The December 1973 Survey of Psychological Operations in Vietnam mentions that “Fountain Pen” was still operational as late as 1973. It says in part:

After the Paris Agreements were signed earlier this year, most leaflet operations were halted. The Royal Lao air Force Operation Fountain Pen, directed against North Vietnamese troops in Laos continued for a period.

Genuine Laos Banknote

Notice the security dots to the left of the tree and by the elephant’s trunk

Communist Counterfeit Laos Banknote

Notice no security dots embedded in the paper

Until very recently, all that was known about these forgeries was that during the war in Laos the Communist forces forged the 1, 5, 10 and 50 kip banknotes of the Kingdom of Laos Banque Nationale du Laos notes of 1957. The forgeries were first said to be printed in Bulgaria and meant to weaken the National Government (Note: the forgeries are described as emanating from Czechoslovakia in Area Handbook for Laos, DA PAM 550-58 1972). The forgeries were good enough to fool the common Lao peasant, but there were some major errors in the printing. For instance, the most noticeable is that the paper of the original banknotes has small colored security dots that are missing in the forgeries. These communist-produced “Vientiane kip” notes were first used to help finance the formation of a short-lived coalition government headed by Prince Souvanna Phouma. In the early 1970s, the replicas were used by the Lao People’s Revolutionary party (whose military arm was the Pathet Lao) as military occupation currency in areas under their control.

A Chinese reference book entitled Contemporary China’s Banknote Printing and Minting for Foreign Countries, China Financial Clearing House, 2000, was found by a specialist in Lao currencies in 2007. The book mentions that the Chinese prepared banknotes for Cuba, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Mongolia. It also states that the Pathet Lao banknotes were printed in the Shanghai banknote printing facility in April 1968, and the banknotes were legal tender in their “liberated” areas. Apparently, there was a secret agreement between the Royal and Pathet Lao governments for each to circulate their own banknotes with the same basic design. The Royal Lao government had their banknotes printed in the United States and the Pathet Lao had theirs printed in China.

In 1970, a former CIA agent stated that his forces captured a cave complex holding the Pathet Lao supply of banknotes. It was a very large number of banknotes and all were flown back to Vientiane. At first, the captured banknotes were going to be overstamped with a propaganda message and dropped over Pathet Lao “liberated” areas, but there were far too many banknotes and too few personnel to do the job. It was then decided to just drop them over the “liberated” areas and ruin the economy with a large amount of currency chasing few goods and services.

This operation led to spurious report of the United States forging Laotian currency. Rumors of a CIA-sponsored forgery project have circulated since the early 1970s. Christopher Robbins, in Air America, Putnam & Sons, 1979, page 132, writes:

Another top secret Agency project involved dropping millions of dollars in forged Pathet Lao currency in an attempt to wreck the economy by flooding it with paper money. Pilots on routine night drops would be asked to return over Communist lines drop several packages. It turned out the packages were full of counterfeit money.

Air American pilot William Wofford said:

We must have dropped two hundred pounds weight of money, hundreds of millions of kip. They were just in paper bags and had these devices the kicker pulled which ignited a small charge and blew the bag apart. The money was packed loosely, and when the bag blew the money would scatter and drift all over the area. I’m sure a few people ate well the next day. When we got back to Vientiane, we had to spend two hours cleaning the airplane because some of the bags burst before we could get them out and we had counterfeit money from one end of the airplane to the other.

A pilot told me:

The C-130A's at Naha, Okinawa, had several different missions dropping PSYOP leaflets in Vietnam, North Vietnam and Laos; and counterfeit currency in North Vietnam. All of the leaflets were printed in Okinawa.

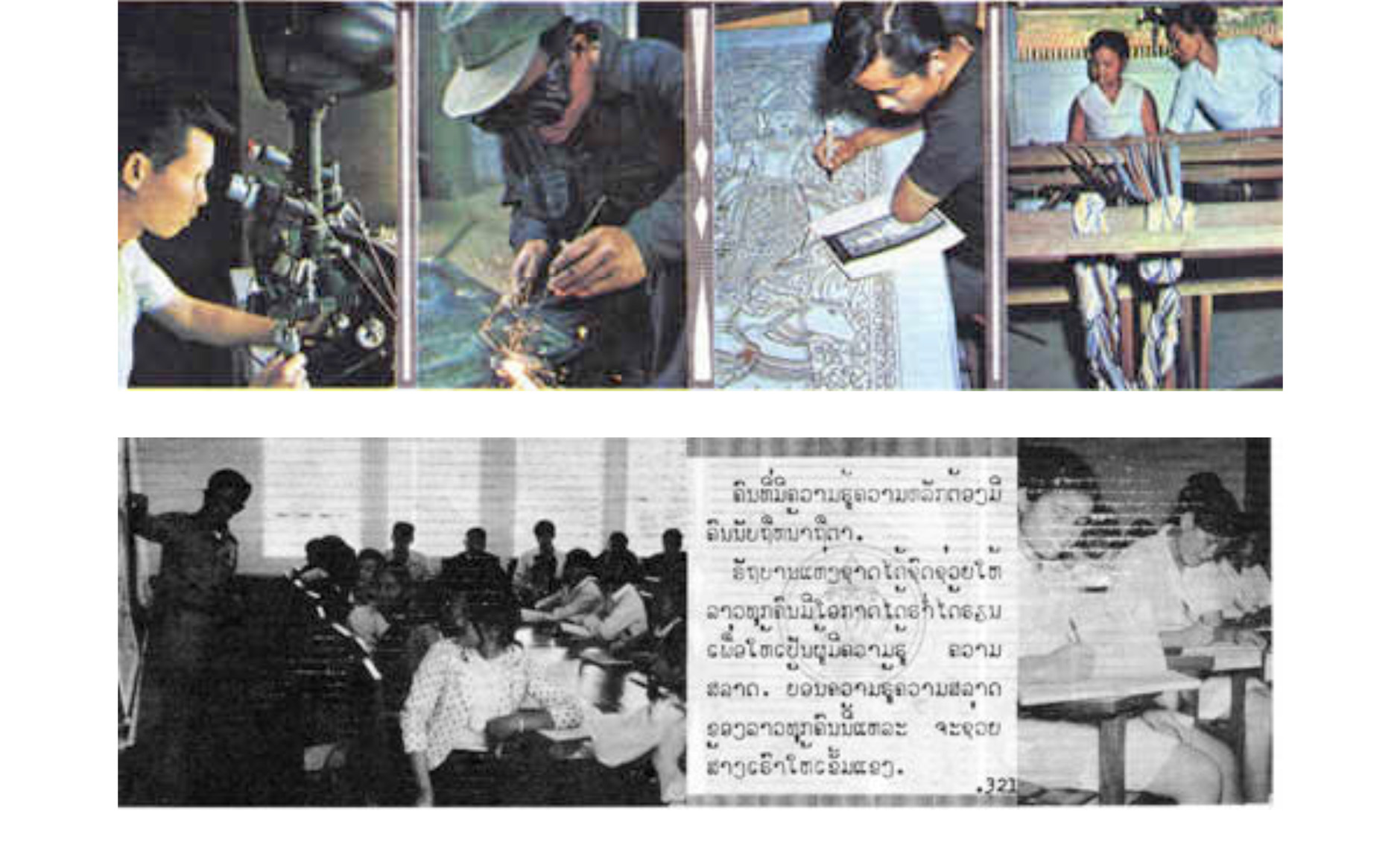

The United States produced a great number of general nation-building leaflets in support of the Royal Laotian government in their fight against the Communist Pathet Lao. The same American PSYOP specialists who were printing leaflets for Vietnam printed many of the Laos leaflets.

Leaflet .22

Leaflet .22 has the Laos symbol in bright red at the left and a photograph of a teacher in classroom on the front. The text at the bottom of the photo is:

Besides studying their normal course work at Ban Ahmone, students also learn community development.

The long text at the left of the photograph is:

National Training Center at Ban Ahmone

This training center is the place where local development training for the people has been carried out for a long time. The people who come here for training include village chiefs, farmers, veterans and good citizens from every province. The course subjects include metal working, wood working, pottery, charcoal making and others. The course subject matter includes agriculture and people who come in for training are able to choose their subjects. When they complete their training, in addition to gaining new skills, they also share their new knowledge with other people in their community.

The back is black and white and depicts three photographs of a workshops and pottery.

Leaflet .43

This leaflet depicts a group of Lao officials visiting what appears to be a Buddhist temple. The text is:

The End of Buddhist Lent

The traditional ceremony to commemorate the end of Buddhist Lent on the full moon of the 11th lunar month every year. Buddhist devotees join together to make offerings to the monks and join in a banquet. In this photograph the monks are receiving alms from the Prince. The evening will be brightly lit with the lights and candles on boats in accordance with the sacred traditions of the Lao since ancient times.

Note: The Buddhist “Lent” starts on the first day of the waning moon of the eighth lunar month. The tradition of Buddhist Lent dates back to the time of early Buddhism in ancient India, All holy men, mendicants and sages spent three months of the annual rainy season in permanent dwellings. They avoided unnecessary travel during the period when crops were still new for fear they might accidentally step on young plants. In deference to popular opinion, Lord Buddha decreed that his followers should also abide by this ancient tradition, and thus began to gather in-groups of simple dwellings.

Leaflet .47

Leaflet .47 depicts a statue of Buddha on the front and the text:

Help to promote Buddhism

Buddhism is the National religion of Laos, and it is the religion the Lao people have respected since ancient times. The Lao people observe the precepts of their religion to make merit for the spirits of their ancestors who have passed on and gone to heaven. We the Lao people must work together to preserve this tradition. Anyone who does anything against the National religion would be acting to destroy their own country.

The back is a long all-text message.

This appears to be rather clever propaganda. The leaflet does not attack the Communists by name, but says that anyone who is against Buddhism is an enemy of the nation. The only enemy of religion was the Communist Pathet Lao, so the people could put two and two together.

Leaflet .58

Leaflet .58 has three photographs on the front; one depicts a farmer, the other two Laotians working with machinery. The text is:

Within Government controlled territory the people have the freedom to pursue their preferred careers.

The back has two photographs of Laotian workers and a longer propaganda text.

Leaflet .64

Leaflet .64 depicts Prince Souvanna Phouma at his desk at the top, and a monk meeting with uniformed officers below. The back depicts three photographs of officials meeting with the people.

His Highness, Prince Souvanna Phouma, leader of the Government, gives his time to the country and the people. He devotes his time to the exceptionally difficult task of promoting peace and bright progress for our Lao Kingdom. All the people must work closely and cooperatively together to build our country to be civilized in the future under the leadership of Prince Souvanna's Government.

Leaflet .67

Leaflet .67 depicts a number of young Laotians boarding a civilian airliner. The back depicts three photographs of a young man looking into a microscope, an engineer and two nurses. The text is:

Why don't you exercise your rights to go and study like them?

The government supports and presents a wide range of opportunities to all Lao people to have the right and freedom to expand their knowledge. Individual intelligence depends on preferences. The government, represented by his Highness Souvannaphouma, is the leader in this effort and has sent Lao students to study in other countries to expand their knowledge in the fields of agriculture, education, transportation, health and other areas. More than 1,000 students have participated to expand their knowledge and experience so they can return to build and develop the country so the future will be brighter and stronger. All Lao citizens at all levels have the right to apply for studies abroad.

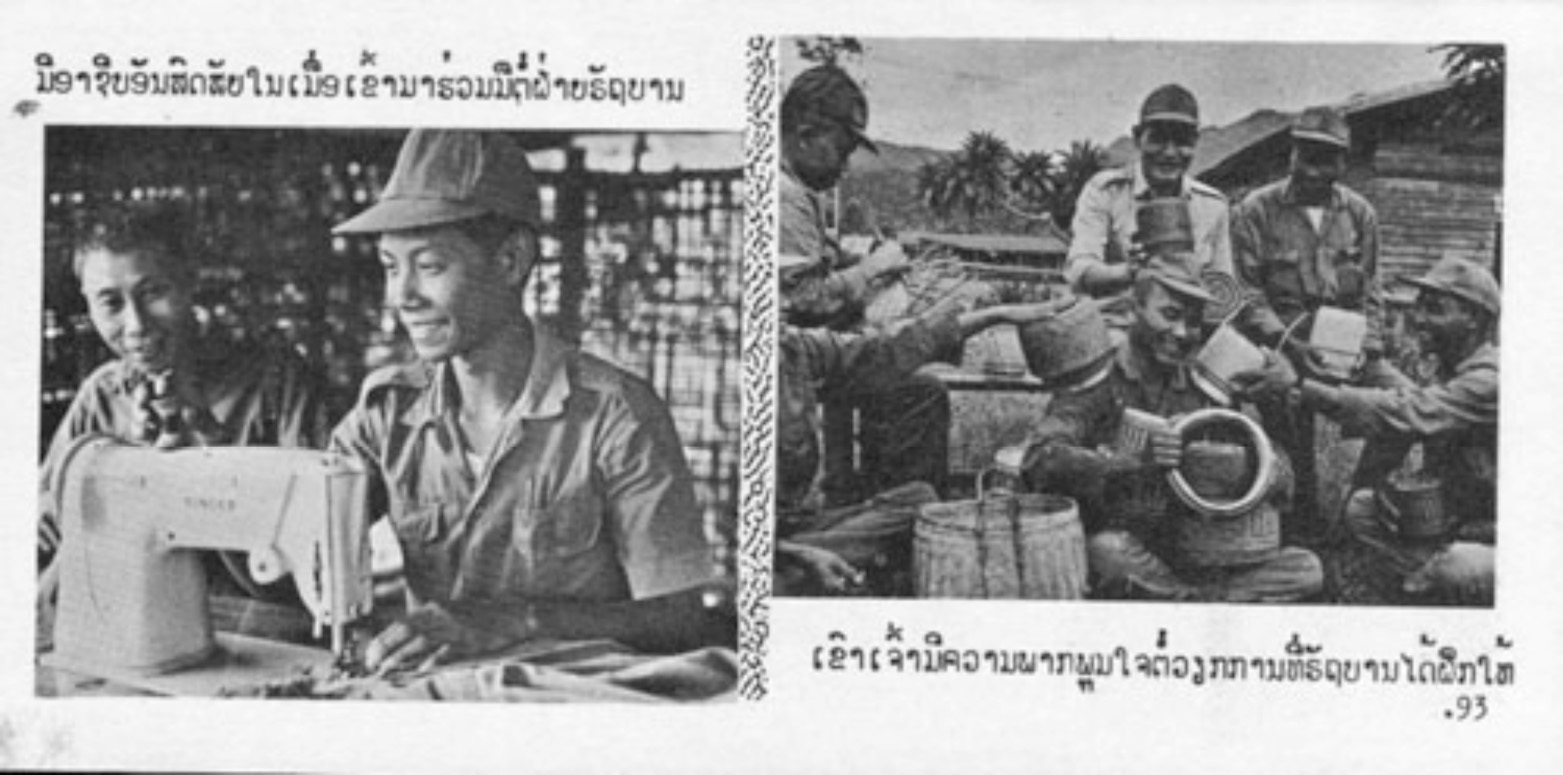

Leaflet .89

This leaflet depicts a Laotian Communist soldier who has rallied to the National Government giving another soldier a haircut. The text is:

New Life with the Government

This former Neo Lao soldier has received training as a barber is from the Royal Lao Armed Forces and he has a good occupation now; more than he had when he was with the Neo Lao. Now he has the right to work and take care of his family.

The back bears two photographs of happy Laotians eating and getting haircuts.

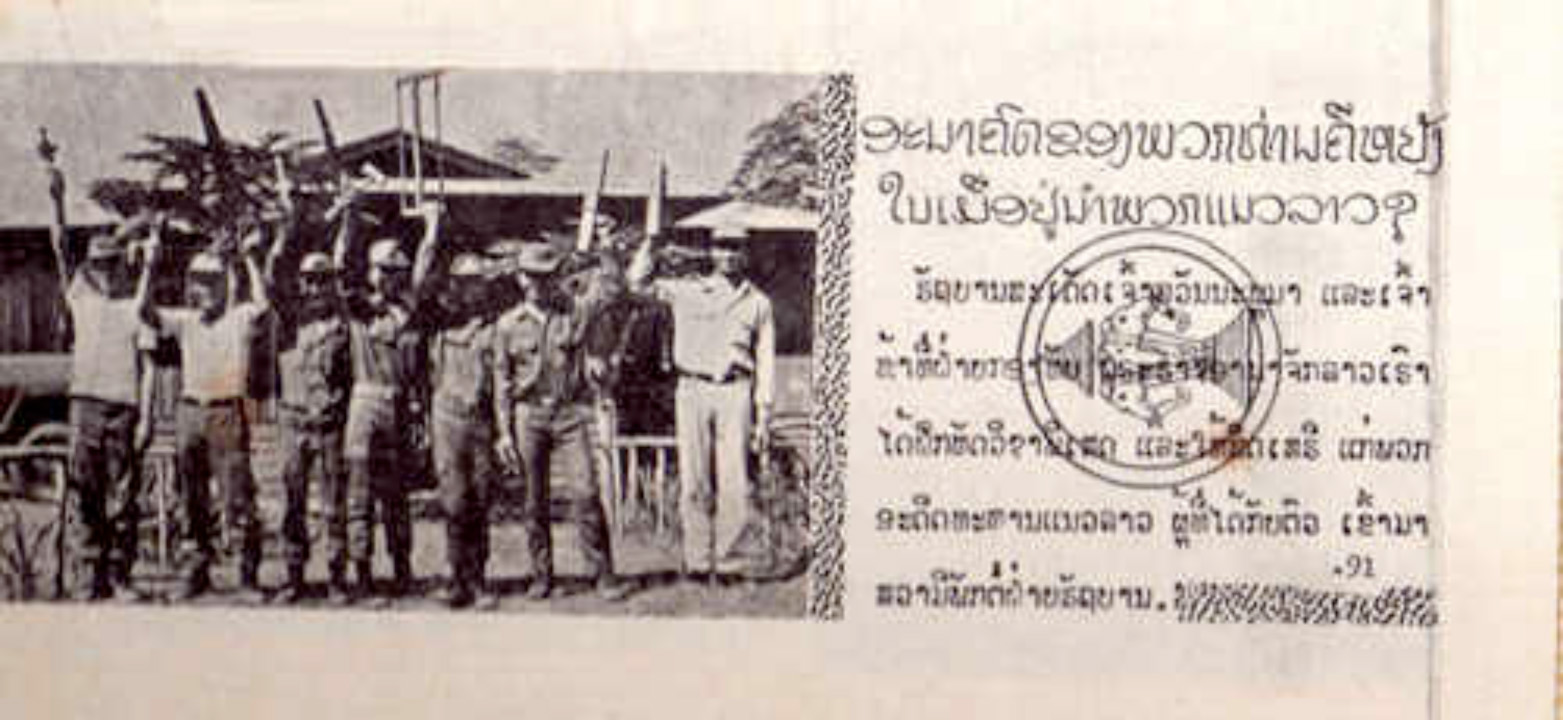

Leaflet .91

The front of Leaflet .91 depicts Laotians working in a carpenter shop. The text is

These are the kinds of job training that Army officials provided for the former Pathet Lao members who surrendered to the National Government

. .

The back of leaflet .91 depicts a group of Laotians holding carpentry tools. The text is: